Basics

Hyperparameters

- The hyperparameters are specified through

TrainingArguments and Seq2SeqTrainingArguments.

model_name_or_path and output_dir are the only two required arguments. However, we should also set other critical hyperparameters, including num_train_epochs, per_device_train_batch_size, per_device_eval_batch_size, learning_rate.

Evaluation, Logging, and Saving

- It is better to set

logging_steps to 1 and logging_strategy to step as logging is beneficial whatsoever yet does not cause significant overhead.

- It is better to specify

eval_steps as 1 / n and eval_strategy to "steps", where n is number evaluations. This will help collect enough samples even if we have fewer training steps or training epochs.

load_best_model_at_end=True has to pair with the following configurations (answer). It will save the best checkpoints according to the evaluations done throughout the training process:

- After setting

eval_steps to a decimal number, save_strategy has to be set to "steps" since save_steps has to be multiple of eval_steps. As saving larger models will take long time, we need to set save_steps to a reasonable number. For example, if we would like to evaluate the model for 10 times (i.e., eval_steps is set to 0.1), we should save twice (i.e., save_steps is set to 0.5).

save_total_limit governs the saving of the latest models; it is likely to save k+1 checkpoints even if save_total_limit=k as the best model is not the latest k models saved.compute_metric has special syntax to follow. For example, the following is taken from the official run_glue.py. Here p.predictions depends on the specific model.

# You can define your custom compute_metrics function. It takes an `EvalPrediction` object (a namedtuple with a

# predictions and label_ids field) and has to return a dictionary string to float.

def compute_metrics(p: EvalPrediction):

preds = p.predictions[0] if isinstance(p.predictions, tuple) else p.predictions

preds = np.squeeze(preds) if is_regression else np.argmax(preds, axis=1)

result = metric.compute(predictions=preds, references=p.label_ids)

if len(result) > 1:

result["combined_score"] = np.mean(list(result.values())).item()

return result

| Index |

Hyperparameter |

Value |

| 1 |

save_strategy, eval_strategy |

steps or epoch; they have to be same. |

| 2 |

eval_steps |

A reasonable value such as 0.1. |

| 3 |

save_steps |

Must be the multiples of the eval_steps. |

| 4 |

metric_for_best_model and compute_metric |

metric_for_best_model defaults to loss (or eval_loss with an automatically prepended eval_). It could be set to other custom metrics defined in compute_metric |

- It is recommended to use

wandb. In order to do so, we need to set report_to and run_name. Note that if we need to use custom name on wandb portal, we should not rename the default output directory.

Testing Training Scripts

| Index |

Hyperparameter |

Value |

Notes |

| 1 |

max_train_samples, max_eval_samples, max_test_samples |

100 |

|

| 2 |

save_strategy |

no |

|

| 3 |

load_best_model_at_end |

False |

|

Checkpoints

If a model has been fine-tuned, then most likely there will be only updates in pytorch_model.bin file. We could reuse the original config.json and the tokenizer.

However, if we save checkpoints during training, then the code of saving checkpoints has already been taken care of.

Inference

langchain, Pipeline, and Model Classes

The classes and methods provided inmodel.generate() ,pipeline (or TextGenerationPipeline) and langchain are increasingly more high-level: the TextGenerationPipeline internally calls model.generate() and langchain.llms.huggingface_pipeline.HuggingFacePipeline internally uses TextGenerationPipeline.

Therefore, it is sufficient to understand how model.generate() works and how the more abstract classes wrap the other classes. See the following example. Note that

-

A better way to specify arguments is not through a dictionary but through a predefined class such as

transformers.GenerationConfig and then model.config = config. This could make the most use of the code reference feature available in PyCharm.

-

We should stick to

transformers.pipeline rather than TextGenerationPipeline as the former has the unified API across different tasks.

-

Here is the decision flow of which API to use:

| Index |

API |

Case |

| 1 |

model.generate() |

When we need special control over the outputs. For example, adding human bias to the distribution similar to logit_bias for OpenAI APIs (example) or transformers.NoBadWordsLogitProcessor. |

| 2 |

transformers.pipeline |

Preferred as the first choice. |

| 3 |

langchain |

When working with langchain |

import os

os.environ["CUDA_VISIBLE_DEVICES"] = str(0)

os.environ["TOKENIZERS_PARALLELISM"] = "false"

import torch

from transformers import (

pipeline,

AutoTokenizer,

AutoModelForCausalLM,

)

from langchain.llms.huggingface_pipeline import (

HuggingFacePipeline,

)

##################################################

model = AutoModelForCausalLM.from_pretrained("gpt2")

tokenizer = AutoTokenizer.from_pretrained("gpt2")

prompt = "Great changes have taken place in the past 30 years"

##################################################

# method 1

# BAD: requires manually moving model and data to the device

config = {

"do_sample": True,

"top_p": 1,

"num_return_sequences": 5,

"temperature": 1,

"max_new_tokens": 16,

}

device = torch.device("cuda:0")

model = model.to(device)

tokenizer.pad_token = tokenizer.eos_token

raw_response1 = model.generate(

**tokenizer(prompt, return_tensors="pt").to(device),

**config,

).squeeze()

texts1 = tokenizer.batch_decode(raw_response1)

##################################################

# method2

# GOOD

config = {

"do_sample": True,

"top_p": 1,

"num_return_sequences": 5,

"temperature": 1,

"max_new_tokens": 16,

"device": "cuda:0"

}

pipeline = pipeline(

"text-generation",

model=model,

tokenizer=tokenizer,

**config

)

response2 = pipeline(prompt)

texts2 = [response["generated_text"] for response in response2]

##################################################

# method 3

# GOOD: However, it could NOT generate multiple sequences at the same time

llm = HuggingFacePipeline(pipeline=pipeline)

texts3 = list()

for _ in range(5):

texts3.append(llm(prompt))

Controlled Generation

Enforcing or Forbidding Specific Tokens

This is done using disjunctive constraints (enforcing) or NoBadWordsLogitsProcessor (forbidding) internally in model.generate(). This could be easily implemented using the snippet below.

Note that when enforcing generation, setting num_beams to an integer greater than 1 is critical as enforcing presence of some tokens is implemented using beam search.

from transformers import AutoTokenizer, AutoModelForCausalLM

def get_tokens_as_list(model_name, word_list):

tokenizer_with_prefix_space = AutoTokenizer.from_pretrained(model_name, add_prefix_space=True)

tokens_list = []

for word in word_list:

tokenized_word = tokenizer_with_prefix_space([word], add_special_tokens=False).input_ids[0]

tokens_list.append(tokenized_word)

return tokens_list

model = AutoModelForCausalLM.from_pretrained("gpt2")

tokenizer = AutoTokenizer.from_pretrained("gpt2")

tokenizer.pad_token_ids = tokenizer.eos_token_id

prompt = "Great changes have taken place in the past 30 years"

inputs = tokenizer(prompt, return_tensors="pt")

output_ids = model.generate(inputs["input_ids"], max_new_tokens=5)

print(tokenizer.batch_decode(output_ids, skip_special_tokens=True)[0])

words_ids = get_tokens_as_list(model_name="gpt2", word_list=["Donald", "Trump"])

output_ids = model.generate(inputs["input_ids"], max_new_tokens=5, bad_words_ids=words_ids)

print(tokenizer.batch_decode(output_ids, skip_special_tokens=True)[0])

output_ids = model.generate(inputs["input_ids"], max_new_tokens=5, force_words_ids=words_ids, num_beams=10)

print(tokenizer.batch_decode(output_ids, skip_special_tokens=True)[0])

Inference on Multiple Devices

It does not seem to easily make inferences on multiple devices. However, we could use optimized attention implemented torch>=2.0.0 and optimum to reduce the time and space requirement.

Instruction Tuning

Using the Basic transformers Library

It is possible to instruction-tune a language model using the official example script run_clm.py working with gpt2 or the Phil Schimid’s blog working with google/flan-t5-xl.

Using the trl Library

SFTTrainer() provided in the trl provides an another layer of abstraction; this makes instruction-tuning even easier and cleaner. However, the downsides are (1) it could not work well with deepspeed, and (2) it does not support everything (for example, setting save_steps to a decimal number) defined in transformers.TraingingArguments; this limits its flexibility.

-

Tuning a Model with the Language Modeling Objective

This could be done in fewer than 14 lines of code. For example, tuning an LM on the imdb dataset. We could add more configurations to the code skeleton below (for example, PEFT, 4-bit / 8-bit) following the example script here.

from datasets import load_dataset

from transformers import AutoModelForCausalLM

from trl import SFTTrainer

dataset = load_dataset("imdb", split="train")

model = AutoModelForCausalLM.from_pretrained("facebook/opt-350m")

trainer = SFTTrainer(

model,

train_dataset=dataset,

dataset_text_field="text",

max_seq_length=512,

)

trainer.train()

- Tuning a Model using the Completions – Self-Instruction

Tuning Large Models with Constrained Hardware

Overview

We have the following decision matrix when we are working on the single node; there may be other considerations when working with multiple nodes; a node means a machine’s GPUs are physically connected.

|

Single GPU |

Multiple GPUs |

| Mode Fits into Single GPU |

– |

DDP

ZeRO (may or may not be faster) |

| Model Does not Fit into Single GPU |

ZeRO + Offload CPU + MCT (optional) + NVMe (optional) |

PP (preferred) if NVLink or NVSwitch is not available

ZeRO

TP |

| Largest Layer Does not Fit into Single GPU |

ZeRO + Offload CPU + MCT + NVMe (optional) |

TP

ZeRO + Offload CPU + MCT + NVMe (optional) |

Using a Single GPU

- A typical model with AdamW optimizer requires 18 bytes per parameter.

-

Besides the methods described below, one could try

accelerate library to use same torch code for any hardware configuration (CPU, single GPU, and multiple GPUs).

-

Besides the methods described below, one could try

accelerate library to use same torch code for any hardware configuration (CPU, single GPU, and multiple GPUs).

| Method |

Speed📈 |

Memory📉 |

Note |

| Batch Size |

Yes |

Yes |

It should be default to 8. But choosing a batch size that makes most of GPUs is complicated. |

| Dataloader |

Yes |

No |

Always set pin_memory=True andnum_workers=4 (or 8, 16, …) when possible. |

| Optimizer |

Yes |

Yes |

Using Adafactor saves 50% compared to Adam or AdamW. But it does not converge fast. This is supported out-of-box.

One could alternatively use 8-bit AdamW to save more than 50% memory when bibsandbytes is installed and used. |

| Gradient Checkpointing |

No |

Yes |

Supported by Trainer(..., gradient_checkpointing=True, ...). |

| Gradient Accumulation |

No |

Yes |

Supported by Trainer(..., gradient_accumulation_steps=4,...). |

| Mixed Precision Training |

Yes |

No |

fp16 is supported in TrainingArguments(.., fp16=True, ...).

With Ampere GPUs such as A100 or RTX-3090, bf16=True or tf32=True (with torch.beakends.cuda.mamul.allow_tf32=True) could be set. |

| DeepSpeed ZeRO |

No |

Yes |

The model with the smallest batch size does not fit into the GPU. Using Trainer() is supported out-of-box. |

We could use the code below to measure the GPU utilization:

from pynvml import *

def print_gpu_utilization():

nvmlInit()

handle = nvmlDeviceGetHandleByIndex(0)

info = nvmlDeviceGetMemoryInfo(handle)

print(f"GPU memory occupied: {info.used//1024**2} MB.")

For example, when tuning a bert-large-uncased model with some dummy data, we could see on top of the following vanilla code:

- Vanilla Code to Tune a Classification Model

import os

os.environ["CUDA_VISIBLE_DEVICES"] = str(0)

import numpy as np

from datasets import Dataset

from transformers import (

Trainer,

logging,

TrainingArguments,

AutoModelForSequenceClassification,

)

from utils.common import print_gpu_utilization

##################################################

logging.set_verbosity_error()

dataset_size, seq_len = 512, 512

train_dataset = Dataset.from_dict(

{

"input_ids": np.random.randint(100, 30000, (dataset_size, seq_len)),

"labels": np.random.randint(0, 1, dataset_size),

}

)

train_dataset.set_format("pt")

print_gpu_utilization()

##################################################

default_args = {

"output_dir": "tmp",

"evaluation_strategy": "steps",

"num_train_epochs": 1,

"log_level": "error",

"report_to": "none"

}

training_args = TrainingArguments(

per_device_train_batch_size=4,

**default_args

)

model = AutoModelForSequenceClassification.from_pretrained("bert-large-uncased").to("cuda")

print_gpu_utilization()

trainer = Trainer(

model=model,

args=training_args,

train_dataset=train_dataset

)

result = trainer.train()

After making updates to the vanilla code, we could see the changes in the memory usage.

| Basic Setup |

Memory (MB) |

| Loading Dummy Data |

2631 |

| Loading Model with per_device_train_batch_size=4 |

14949 |

| Loading Model with per_device_train_batch_size=4 + 8-bit Adam |

13085 |

| Loading Model with per_device_train_batch_size=4 + optim=”adafactor” |

12295 |

| Loading Model with per_device_train_batch_size=4 + fp16=True |

13939 |

| Loading Model with per_device_train_batch_size=4 + fp16=True + gradient_checking=True |

7275 |

| Loading Model with per_device_train_batch_size=1 + gradient_accumulation_steps=4 |

8681 |

| Loading Model with per_device_train_batch_size=1 + gradient_accumulation_steps=4+ gradient_checkpointing=True |

6775 |

| Loading Model with per_device_train_batch_size=1 + gradient_accumulation_steps=4+ gradient_checkpointing=True + fp16=True and using accelerate. |

5363 |

Using Multiple GPUs

There are data, tensor, and pipeline parallelism when working with multiple GPUs. Each of them has pros and cons, there does not exist an universally good solution that fits into any situation.

According to Jason Phang, the ZeRO is the more efficient method than PEFT and PP:

There ought to be more efficient methods of tuning (DeepSpeed / ZeRO, NeoX) than the ones presented here, but folks may find this useful already.

Reference

| Index |

Name |

Note |

| 1 |

https://huggingface.co/docs/transformers/perf_train_gpu_one |

Official Tutorial |

| 2 |

https://huggingface.co/docs/transformers/perf_train_gpu_many |

Official Tutorial |

| 3 |

https://github.com/zphang/minimal-llama |

Jason Phang |

| 4 |

https://huggingface.co/docs/transformers/main_classes/deepspeed |

HuggingFace Documentation |

| 5 |

https://huggingface.co/blog/4bit-transformers-bitsandbytes |

Fine-Tuning LLMs like llama, gpt-neox, and t5. |

| 6 |

https://huggingface.co/blog/pytorch-ddp-accelerate-transformers |

Official Tutorial |

Using simpletransformers

Comparing transformers and simpletransformers

simpletransformers is a wrapper of transformers that abstracts out some unnecessary details for training and inference a wide array of models, including text classification (multi-class and multi-label) and regression.

The number of lines of code is significantly reduced if we switch from transformers to simpletransformers. For example, the code below tries to make a inference using bert-base-uncased on a safety dataset:

import os

os.environ["WANDB_DISABLED"] = "true"

os.environ["TOKENIZERS_PARALLELISM"] = "false"

import numpy as np

import pandas as pd

from sklearn.metrics import (

classification_report,

)

from datasets import (

Dataset,

load_dataset

)

from transformers import (

Trainer,

AutoTokenizer,

TrainingArguments,

default_data_collator,

AutoModelForSequenceClassification,

)

model_name = "distilbert-base-uncased-finetuned-sst-2-english"

dataset = load_dataset("glue", "sst2", split="validation")

model = AutoModelForSequenceClassification.from_pretrained(model_name)

tokenizer = AutoTokenizer.from_pretrained(model_name)

tokenized_dataset = dataset.map(

lambda x: tokenizer(x["sentence"], padding="max_length", truncation=True, max_length=256),

)

training_args = TrainingArguments(

output_dir="outputs",

per_device_eval_batch_size=256,

remove_unused_columns=True,

)

trainer = Trainer(

model=model,

tokenizer=tokenizer,

args=training_args,

data_collator=default_data_collator,

)

y_pred = np.argmax(trainer.predict(tokenized_dataset).predictions, axis=1)

y_true = dataset["is_safe"]

print(classification_report(

y_true=y_true,

y_pred=y_pred

))

By comparison, we could obtain the exactly same results with simpletransformers:

import os

os.environ["WANDB_DISABLED"] = "true"

os.environ["TOKENIZERS_PARALLELISM"] = "false"

from sklearn.metrics import (

classification_report,

)

from datasets import (

load_dataset

)

from simpletransformers.classification import (

ClassificationModel,

ClassificationArgs,

)

model_name = "distilbert-base-uncased-finetuned-sst-2-english"

dataset = load_dataset("glue", "sst2", split="validation")

model_args = ClassificationArgs()

model_args.eval_batch_size = 256

model_args.max_seq_length = 256

model_args.use_multiprocessing = False

model_args.use_multiprocessing_for_evaluation = False

model = ClassificationModel(

model_type="distilbert",

model_name=model_name,

num_labels=2,

args=model_args,

)

y_pred, _ = model.predict(dataset["sentence"])

y_true = dataset["label"]

print(classification_report(

y_true=y_true,

y_pred=y_pred

))

Minimal Working Example

simpletransformers could more quickly and cleanly train and evaluate PLMs compared to transformers, where the simpletransformers library is based upon; it also comes with full support from wandb. Note that

- The number of steps is computed based on one GPU even though

model_args.n_gpu is set to a different value. Therefore, we should not further divide n_total_steps by model_args.n_gpu.

- By default, there will be evaluations at the end of each epoch. Therefore, setting

n_eval=10 will lead to model_args.num_epochs + n_eval evaluations; in the example below, there will be 13 evaluations.

The following example fine-tunes bert-base-uncased on the imdb dataset:

import os

os.environ["TOKENIZERS_PARALLELISM"] = "false"

import pandas as pd

from datasets import load_dataset

from sklearn.model_selection import train_test_split

from simpletransformers.classification import (

ClassificationModel,

ClassificationArgs

)

model_args = ClassificationArgs()

model_class = "roberta"

model_name = "roberta-base"

##################################################

# see full list of configurations:

# https://simpletransformers.ai/docs/usage/#configuring-a-simple-transformers-model

# critical settings

model_args.learning_rate = 1e-5

model_args.num_train_epochs = 3

model_args.train_batch_size = 32

model_args.eval_batch_size = 32

model_args.gradient_accumulation_steps = 1

model_args.fp16 = False

model_args.max_seq_length = 128

model_args.n_gpu = 4

model_args.use_multiprocessing = False

model_args.use_multiprocessing_for_evaluation = False

# saving settings

model_args.no_save = False

model_args.overwrite_output_dir = True

model_args.output_dir = "outputs/"

# the following mandates that only the best checkpoint will be saved; there will be only 1 checkpoint

model_args.best_model_dir = "{}/best_model".format(model_args.output_dir)

model_args.save_model_every_epoch = False

model_args.save_best_model = True

model_args.save_eval_checkpoints = False

model_args.save_steps = -1

# validation criterion

model_args.use_early_stopping = False

model_args.early_stopping_metric = "auroc"

model_args.early_stopping_metric_minimize = False

# evaluation settings

model_args.evaluate_during_training = True

# logging settings

model_args.silent = False

model_args.wandb_project = "simpletransformers"

model_args.wandb_kwargs = {

"name": "sanity-check-imdb"

}

##################################################

# loading dataset

ds = load_dataset("imdb")

# data splits

# there has to be "text" and "labels" columns in the input dataframe

df = pd.DataFrame(ds["train"]).rename(columns={"label": "labels"})

train_df, eval_df = train_test_split(df.sample(frac=0.1), test_size=0.2)

test_df = pd.DataFrame(ds["test"]).sample(frac=0.1).rename(columns={"label": "labels"})

##################################################

# adaptive steps settings

# we will evaluate 10 times and log 100 times no matter how small the dataset

n_eval, n_log = 10, 100

n_total_steps = round(len(train_df) / model_args.train_batch_size) * model_args.num_train_epochs

model_args.evaluate_during_training_steps = max(1, round(n_total_steps / n_eval))

model_args.logging_steps = max(1, round(n_total_steps / n_log))

model_args.save_steps = -1

##################################################

# training

model = ClassificationModel(

model_class,

model_name,

num_labels=2,

args=model_args,

)

model.train_model(

train_df=train_df,

eval_df=eval_df

)

# test

result, model_outputs, wrong_predictions = model.eval_model(test_df)

Validation and Early Stopping

-

Validation

Choosing which model checkpoint to save (aka. validation) depends on early_stopping_metric and early_stopping_metric_minimize even though early stopping itself is disabled.

-

Early Stopping

If we need to use early stopping, we need to also be aware of the other hyperparameters.

| Name |

Default |

Note |

use_early_stopping |

False |

|

early_stopping_metric |

"eval_loss" |

eval_during_training has to be True; it will use metrics computed during evaluation. |

early_stopping_metric_minimize |

True |

|

early_stopping_consider_epochs |

False |

|

early_stopping_patience |

3 |

Terminate training after early_stopping_patience evaluations without improvement specified byearly_stopping_delta. |

early_stopping_delta |

0 |

|

class ClassificationModel:

def train_model(

self,

train_df,

multi_label=False,

output_dir=None,

show_running_loss=True,

args=None,

eval_df=None,

verbose=True,

**kwargs,

):

// ...

global_step, training_details = self.train(

train_dataloader,

output_dir,

multi_label=multi_label,

show_running_loss=show_running_loss,

eval_df=eval_df,

verbose=verbose,

**kwargs,

)

// ...

def train(

self,

train_dataloader,

output_dir,

multi_label=False,

show_running_loss=True,

eval_df=None,

test_df=None,

verbose=True,

**kwargs,

):

//...

best_eval_metric = None

// ...

if not best_eval_metric:

best_eval_metric = results[args.early_stopping_metric]

self.save_model(

args.best_model_dir,

optimizer,

scheduler,

model=model,

results=results,

)

// ...

Using Sentence-Transformers

Overview

sentence_transformer is built with torch despite a resemblance to the keras API.- The famous METB benchmark is also largely built on top of the

sentence_transformer library.

Fine-Tuning Embeddings

Besides an easy interface to generate embeddings, the sentence_transformers library also supports fine-tuning the provided embedding models. The following data formats all have their corresponding loss functions without a need to convert data to a specific format (for example, triplets) (see blog).

Note that these loss functions come from the sentence_transformers library rather than torch or transformers. These loss functions have been discussed in a blog post that is not affiliated with the developers of sentence_transformers.

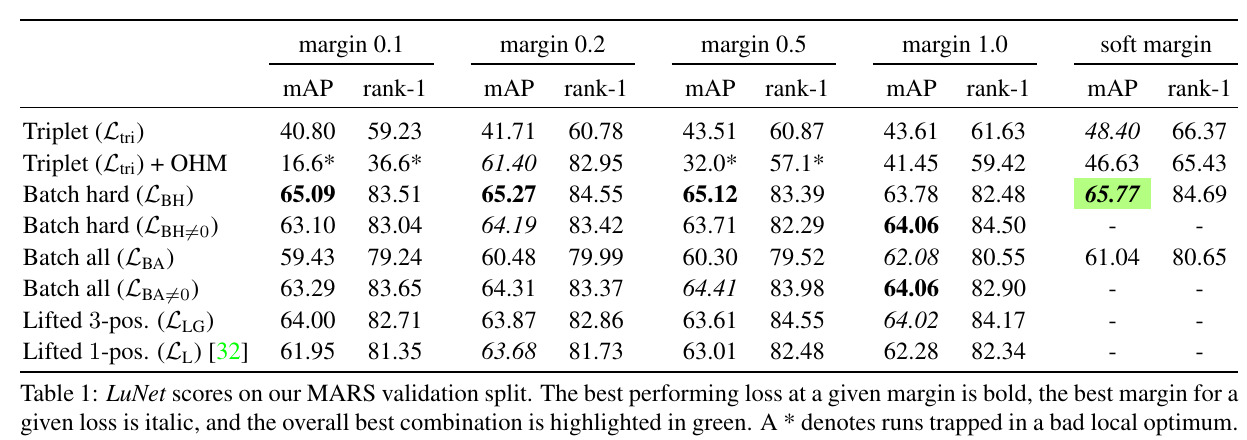

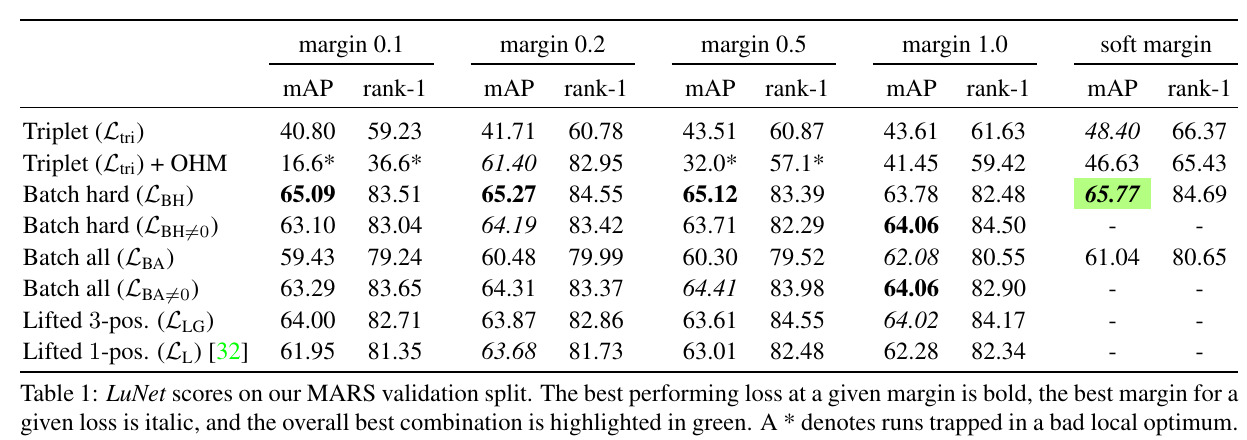

| Index |

Description |

Data |

Loss |

Note |

| 1 |

A pair of sentences and a label |

(premise, hypothesis, label) |

ContrastiveLoss;

SoftmaxLoss;

CosineSimilarityLoss |

|

| 2 |

Individual sentence and corresponding label |

(text, label) |

BatchHardTripletLoss and variants |

“batch hard” performs best in the blog post. |

| 3 |

A pair of similar sentences |

(query, response), (src_lang, tgt_lang), (full_text, summary), (text1, text2) (e.g., QQP), (text, entailed_text) (e.g., NLI) |

MultipleNegativeRankingLoss;

MegaBatchMarginLoss |

Frequent |

| 4 |

A triplet of sentences of an positive, a positive, and a negative |

(anchor, positive, negative) |

TripletLoss |

Rare as it requires offline mining |

Here is a minimal working example of fine-tuning representation using sst2 dataset; we could optionally evaluate the fine-tuned model on the MTEB benchmark as it is also built with sentence_transformer library.

Note that:

import os

import wandb

import random

import logging

import pandas as pd

from datetime import datetime

from collections import defaultdict

from sentence_transformers import (

SentenceTransformer,

InputExample,

SentencesDataset

)

from sentence_transformers.evaluation import (

TripletEvaluator,

)

from sentence_transformers import LoggingHandler

from sentence_transformers.losses import (

BatchHardTripletLoss,

)

from datasets import load_dataset

from torch.utils.data import DataLoader

logging.basicConfig(

format="%(asctime)s - %(message)s",

datefmt="%Y-%m-%d %H:%M:%S",

level=logging.INFO,

handlers=[LoggingHandler()],

)

def triplets_from_labeled_dataset(

records,

text_column="sentence",

label_column="label"

):

# Create triplets for a [(label, sentence), (label, sentence)...] dataset

# by using each example as an anchor and selecting randomly a

# positive instance with the same label and a negative instance with a different label

input_examples = [

InputExample(guid=str(guid), texts=[record[text_column]], label=record[label_column])

for guid, record in enumerate(records)

]

triplets = []

label2sentence = defaultdict(list)

for inp_example in input_examples:

label2sentence[inp_example.label].append(inp_example)

for inp_example in input_examples:

anchor = inp_example

if len(label2sentence[inp_example.label]) < 2: #We need at least 2 examples per label to create a triplet

continue

positive = None

while positive is None or positive.guid == anchor.guid:

positive = random.choice(label2sentence[inp_example.label])

negative = None

while negative is None or negative.label == anchor.label:

negative = random.choice(input_examples)

triplets.append(InputExample(texts=[anchor.texts[0], positive.texts[0], negative.texts[0]]))

return triplets

##################################################

model_name = 't5-base'

num_epochs = 10

##################################################

current_time = datetime.now().strftime("%Y-%m-%d_%H-%M-%S")

wandb.init(

project="sentence_transformers",

name=f"{model_name}-{current_time}"

)

##################################################

# model

output_path = (

"output/"

+ model_name

+ "-"

+ current_time

)

model = SentenceTransformer(model_name)

##################################################

def get_dataloader(df, split, text_column, label_column, batch_size=8):

records = df.to_dict("records")

examples = [

InputExample(texts=[record[text_column]], label=record[label_column])

for record in records

]

dataset = SentencesDataset(

examples=examples,

model=model,

)

dataloader = DataLoader(dataset, shuffle=True, batch_size=batch_size)

return dataloader

##################################################

# data

ds = load_dataset("sst2")

train_df = pd.DataFrame(ds["train"])

val_df = pd.DataFrame(ds["validation"])

test_df = pd.DataFrame(ds["test"])

train_dataloader = get_dataloader(train_df, "train", text_column="sentence", label_column="label")

##################################################

train_loss = BatchHardTripletLoss(model=model)

val_evaluator = TripletEvaluator.from_input_examples(

triplets_from_labeled_dataset(val_df[["sentence", "label"]].to_dict("records")),

name="eval"

)

val_evaluator(model)

##################################################

def log_with_wandb(score, epoch, steps):

# https://docs.wandb.ai/ref/python/log

wandb.log(

data={"score": score},

step=steps,

)

warmup_steps = int(len(train_dataloader) * num_epochs * 0.1) # 10% of train data

model.fit(

[(train_dataloader, train_loss)],

show_progress_bar=True,

epochs=num_epochs,

evaluator=val_evaluator,

evaluation_steps=50,

warmup_steps=warmup_steps,

output_path=output_path,

callback=log_with_wandb

)

##################################################

test_evaluator = TripletEvaluator.from_input_examples(

triplets_from_labeled_dataset(test_df[["sentence", "label"]].to_dict("records")),

name="test"

)

model.evaluate(test_evaluator)

As our goal is not evaluating triplets but the quality of clustering, we could define our own evaluator.

from sklearn.cluster import KMeans

from sklearn.metrics import v_measure_score

from sentence_transformers.evaluation import (

SentenceEvaluator,

)

class ClusteringEvaluator(SentenceEvaluator):

def __init__(self, texts, labels, batch_size=32, show_progress_bar=False):

self.texts = texts

self.labels = labels

self.batch_size = batch_size

self.show_progress_bar = show_progress_bar

def __call__(self, model, output_path: str = None, epoch: int = -1, steps: int = -1):

embeddings = model.encode(

self.texts, batch_size=self.batch_size, show_progress_bar=self.show_progress_bar, convert_to_numpy=True

)

y_pred = KMeans(n_clusters=len(set(self.labels)), n_init="auto").fit_predict(embeddings)

score = v_measure_score(

labels_true=self.labels,

labels_pred=y_pred

)

return score

Customization

Saving Checkpoints

Similar to simpletransformers, sentence_transformer could save best checkpoints according to the evaluation metric. Model saving are controlled by _eval_during_training() and _save_checkpoint() functions.

Loss Functions

According to the doc, we should choose which loss to use based on the available format of data we have. There are 14 loss functions supported by sentence_transformer.

| Index |

Loss Function |

Data Format |

Publication |

Note |

| 1 |

BatchAllTripletLoss |

(text, label) |

1 |

Using all positive and negative within the PK batch; leading to PK\cdot (PK-K) \cdot (K-1) pairs. |

| 2 |

BatchSemiHardTripletLoss |

(text, label) |

1 |

|

| 3 |

BatchHardTripletLoss |

(text, label) |

1 |

Finding the hardest positive and negative within the PK batch, leading to PK pairs. |

| 4 |

BatchHardSoftMarginTripletLoss |

(text, label) |

1 |

Replacing the hinge function with a softplus function. |

| 5 |

ConstrativeLoss |

(text1, text2, label) |

4 |

|

| 6 |

OnlineContrastiveLoss |

(text1, text2, label) |

4 |

|

| 7 |

SoftmaxLoss |

(text1, text2, label) |

2 |

|

| 8 |

CosineSimilarityLoss |

(text1, text2, similarity) |

|

|

| 9 |

DenoisingAutoEncoderLoss |

(corrupted text, original text) |

5 |

|

| 10 |

MultipleNegativeRankingLoss |

(anchor, positive) |

8 |

|

| 11 |

MegaBatchMarginLoss |

(anchor, positive) |

7 |

Requires a large batch size (like 500). |

| 12 |

TripletLoss |

(anchor, positive, negative) |

|

Requires Offline Hard Mining (OHM) described in 1. |

| 13 |

MSELoss |

(src embedding, tgt embedding) |

3 |

Aligning embeddings of multiple languages. |

| 14 |

MarginMSELoss |

(a, p, n, d(a, p), d(a, n)) |

6 |

Very stringent requirement for input data. |

-

[1703.07737] In Defense of the Triplet Loss for Person Re-Identification: This paper overturns the prevailing belief that the a more intuitive triplet loss is worse than the surrogate classification loss by proposing new loss functions; it also critically points out the limitations of the

TripletLoss:

A major caveat of the triplet loss, though, is that as the dataset gets larger, the possible number of triplets grows cubically, rendering a long enough training impractical. To make matters worse, f _ \theta relatively quickly learns to correctly map most trivial triplets, rendering a large fraction of all triplets uninformative.

The goal of metric learning is to preserve the "semantic distance" in the metric space: two semantically similar sentences should be close in the metric space and two dissimilar ones should be remote to each other in the embedding space.

Overall, the "batch-hard" version, possibly with a soft margin, performs best among all loss functions.

-

[1908.10084] Sentence-BERT: Sentence Embeddings using Siamese BERT-Networks

-

[2004.09813] Making Monolingual Sentence Embeddings Multilingual using Knowledge Distillation

-

Dimensionality Reduction by Learning an Invariant Mapping (CVPR 2006, Yann LeCun)

-

[2104.06979] TSDAE: Using Transformer-based Sequential Denoising Auto-Encoder for Unsupervised Sentence Embedding Learning

-

[2010.02666] Improving Efficient Neural Ranking Models with Cross-Architecture Knowledge Distillation

-

ParaNMT-50M: Pushing the Limits of Paraphrastic Sentence Embeddings with Millions of Machine Translations (Wieting & Gimpel, ACL 2018)

-

[1705.00652] Efficient Natural Language Response Suggestion for Smart Reply: Section 4.4 defines the multiple negative loss.

RLHF with trl Library

The trl library provides a one-stop solution to instruction tuning (i.e., SFT), reward modeling, and PPO. The library supports peft and 4-bit (or 8-bit) tuning natively so that we could tune an LM on the customer device.

The trl defines a custom class AutoModelForCausalLMWithValueHead and AutoModelForSeq2SeqMWithValueHead so that the PPO could be done; it returns an unbounded score (through nn.Linear(hidden_size, 1)) for each returned token.

ICL with Long Prompt

There are several solutions to long-prompt generation, including Alibi and Yarn.

-

Yarn

As of 2023-11-22, we have an open-source model of 128K context window. This does not mean that we could do in-context learning with arbitrary number of shots. There is a major gap between the paper and the real-world application: both model and data will consume graphic memory and the memory required for data scales with context length (see an explanation here); however, the paper performs evaluation using a surrogate metric; the authors show that they could successfully work with a context window of 128K by computing the perplexity with a sliding window.

-

Alibi

mosaicml/mpt-7b-8k-instruct, mosaicml/mpt-7b-8k-chat, and mosaicml/mpt-7b-8k.mosaicml/mpt-7b-storywriter: This model could extrapolate beyond 65K tokens.

-

LLongMA