Contents

Problem Statement

The paper [2] notes the difficulty of optimizing the query for neural retrieval models.

However, neural systems lack the interpretability of bag-of-words models; it is not trivial to connect a query change to a change in the latent space that ultimately determines the retrieval results.

The query generation aims to find out “what should have been asked” for a given passage. More formally, if we have a list of documents D that are aligned with our goal (or true underlying query) q, is it possible to search for its approximated version \hat{q} that returns D as relevant documents with high probability?

Background

-

Rocchio Algorithm for Query Expansion

Rocchio algorithm is used by search engines in the backend to improve the user’s initial search queries. For example, if the initial search query is “beaches in Hawaii,” if the backend finds that many users click webpages (this is one type of pseudo relevance feedback, PRF) that contain the word “sunset,” then the word “sunset” will be added to the initial search query, making the real search query “beaches in Hawaii sunset.”

There could be more nuanced PRFs than binary click and not-click action. For example, how long the users stay on a webpage, whether the user eventually returns to the search result page.

Adolphs et al., EMNLP 2022

There are two contributions of this paper:

- Query Inverter: An inverter that converts embeddings back to queries.

- Query Generation: A way to refine the initial generic query (plus a gold document) so that the gold passage will become one of the top ranked documents given a refined query.

Query Inverter

The authors use the GTR model to generate embeddings from 3M queries from the PAQ dataset [5], thus forming a datasets {{(q_i, \mathbf{e}_i)}} _ {i=1} ^ N. Then the authors fine-tune a T5-base decoder by reversing GTR’s input and output as {{ (\mathbf{e} _ i, q_i) }} _ {i = 1} ^ N; this process of fine-tuning T5-base requires 130 hours on 16 TPU v3

- Note: The major limitation of this process is that the fine-tuned T5-base could only invert the embeddings of a fixed GTR model. When working with a GTR model fint-tuned for a new application scenario, the expensive fine-tuning of T5-base has to repeat.

The paper mentions the following interesting application:

We thus evaluate the decoder quality by starting from a document paragraph, decoding a query from its embedding and then running the GTR search engine on that query to check if this query retrieves the desired paragraph as a top-ranked result.

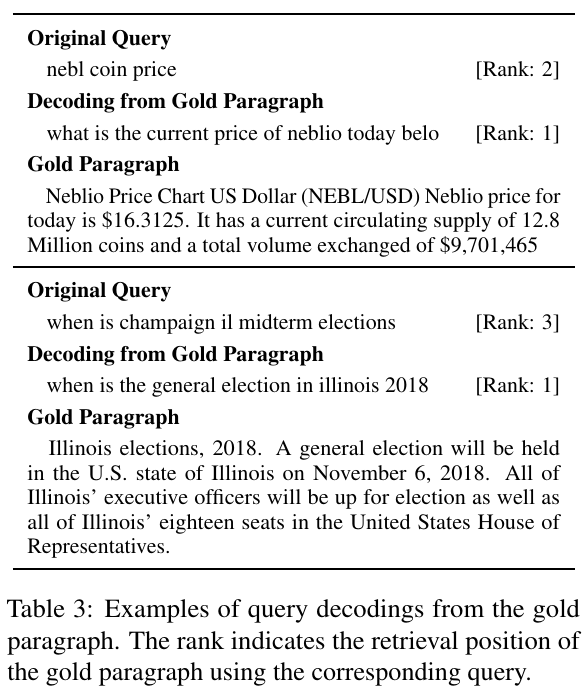

For example, in the sanity check experiment in Table 3, if we use the gold passage to reconstruct the query, and then use this generated query to find relevant passages, the rank of the gold passages improves upon the original approach of querying blindly.

Query Generation

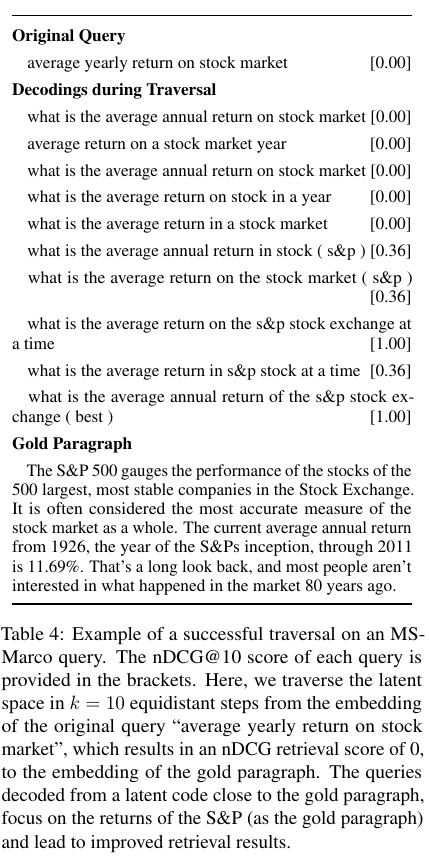

Given an original query \mathbf{q} and a gold document \mathbf{d}, the authors propose to generate new query embedding based on the linear combination of \mathbf{q} and \mathbf{d}; in the experiments, the authors generate select \kappa so that there are 20 new query embeddings.

The intuition of this idea that the optimal query should be between the initial generic (yet relevant) query and the gold passage. The gold passage could be the answer to multiple different questions; we therefore need to use the initial generic query \mathbf{q} to guide the generation of new queries.

\mathbf{q} _ \kappa \leftarrow \frac{\kappa}{k} \mathbf{d} + (1 – \frac{\kappa}{k}) \mathbf{q}

Based on a dataset of succesfully reformulated queries (that is, the gold passage is top ranked by the reformulated query), the authors fine-tune a T5 model with original queries as input and reformulated queries as output; they call this query suggestion model.

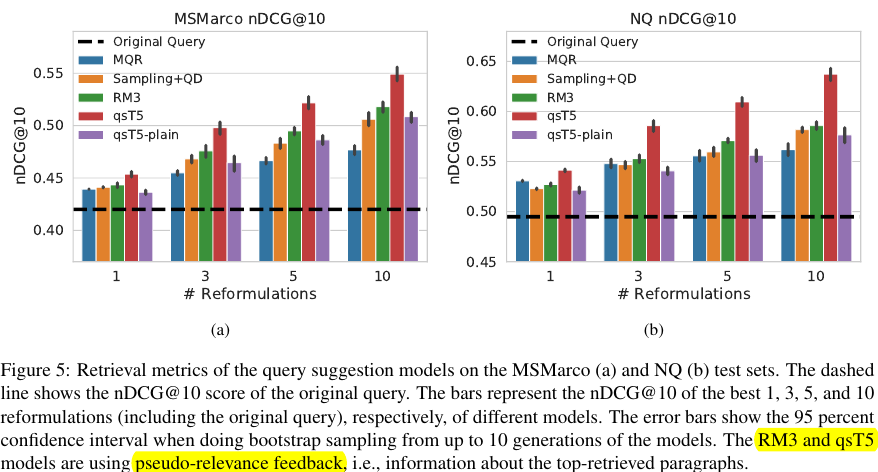

The authors find that their query suggestion models (qsT5 and qsT5-plain) improves the retrieval performance when compared with query expansion baselines, including a strong PRF baseline RM3.

Vec2Text by Cideron et al.

Overview

This paper provides a more high-level motivation to invert embeddings to texts: making semantic decisions in the continuous space (for example, reinforcement learning) to control the output of LLMs; the Morris et al. do not cite this paper but does acknowledge related work in Section 8.

Past research has explored natural language processing learning models that map vectors to sentences (Bowman et al., 2016). These include some retrieval models that are trained with a shallow decoder to reconstruct the text or bag-of-words from the encoder-outputted embedding (Xiao et al., 2022; Shen et al., 2023; Wang et al., 2023). Unlike these, we invert embeddings from a frozen, pre-trained encoder.

The paper reveals the reason why several works focus on inverting the GTR model: the GTR is based on T5 model and it does not have a decoder; it is natural to learn a decoder (as vec2text by Morris et al. and Adolphs et al. have done) that invert embeddings back to texts. Note that the vec2text referred in the text is different from the vec2text developed by Morris et al. despite the same name.

T5 was previously used to learn sentence representation in Ni et al. (2021) where they focus on having a well structure sentence embedding by introducing a contrastive loss to pull together similar sentences and push them away from the negatives. However, Ni et al. (2021) don’t learn a decoder (i.e. a vec2text model) which makes it impossible for them to generate sentences from the embedding space.

Method

This paper uses very similar to the architecture used by Morris et al. and Adolphs et al., it consists of two components

- A Round-Trip Translation (RTT) scheme to prepare the data: the English corpus is first translated to German and back-translated to English; the back-translated English sentences serve as input while the original sentences serve as outputs.

- A T5-base model (same as Adolphs et al. and Morris et al.) with a bottleneck involving (1) mean pooling, and (2) linear projection; this design is similar to Morris et al.’s \mathrm{EmbToSeq}(\mathbf{e}).

However, despite being more high-level (for example, four desired properties), the method in this work is not iterative, which may make this work effective as Morris et al.

Topic Convex Hull

Recall the definition of a convex hull according to he paper proposing the QuickHull algorithm:

The convex hull of a set of points is the smallest convex set that contains the points.

This is a novel concept proposed in this paper. Specifically

- Step 1: Embedding a few sentences known to belong to a specific topic.

-

Step 2: Forming a convex hull using these embeddings. This could be done using

scipy.spatial.ConvexHull(); the underlying algorithm is gift wrapping algorithm in computational geometry (Wikipedia).To form a convex hull, we need to have a matrix (n, d) and n > d. For example, if we want to find a convex hull of BERT embeddings, we need to have at least have 769 samples. This could be prohibitively slow as the runtime of the algorithm is exponential in terms of dimensions O(n ^ {\lfloor d / 2\rfloor}) (doc); empirically, the answer further notes that the routine works for data up to 9 dimensions.

- Step 3: Sampling uniformly with a Dirichlet distribution from the convex hull. This answer provides a Python function to do it; this answer explicitly mentions the Dirichlet distribution; this paper is likely use the same function.

Vec2Text by Morris et al.

Method

Recall the chain rule:

p(a, b, c) = p(a\vert b, c) \cdot p(b\vert c) \cdot p(c)

The proposed approach is inverting an embedding \mathbf{e} from an arbitrary embedding function \phi(\cdot) (for example, OpenAI embedding API) back to text x^{(t+1)} iteratively from an initial guess x^{(0)}. This correction could take multiple steps; the total number of steps should not be large (up to 40).

p\left(x^{(0)}\vert \mathbf{e}\right) = p\left(x^{(0)}\vert \mathbf{e}, \emptyset, \phi(\emptyset)\right) \rightarrow \cdots \rightarrow

p\left(x^{(t+1)} \vert \mathbf{e}\right) = \sum _ {x ^ {(t)}} p\left(x ^ {(t)}\vert \mathbf{e}\right) \cdot \boxed{p\left(x^{(t+1)} \vert \mathbf{e}, x^{(t)}, \phi(x ^ {(t)})\right)}

The boxed term is operationalized as a T5-base model. To make sure an arbitrary embedding fits into the dimension of T5-base, the authors further use a MLP to project arbitrary embeddings of size d to the right size s.

\mathrm{EmbToSeq}(\mathbf{e})=\mathbf{W} _ 2 \sigma(\mathbf{W} _ 1 \mathbf{e})

The authors propose to feed the concatentation of 4 vectors – \mathrm{EmbToSeq}(\mathbf{e}), \mathrm{EmbToSeq}(\mathbf{\hat{e}}), \mathrm{EmbToSeq}(\mathbf{e} – \hat{\mathbf{e}}), and embeddings of x ^ {(t)} using T5-base (the total size input size is 3s + n) to the model and fine-tune the T5-base with regular LM objective.

In the experiments, the authors invert the same model as the GTR model as Adolphs et al. and OpenAI text embedding API; the fine-tuning of each T5-base on each dataset took 2 days on 4 A6000 GPUs.

- Difference from Adolphs et al.

Even though the idea to invert the GTR model and how this inverter is trained is quite similar, Adolphs et al. does not consider the multi-step correction, this seems to be the key to make the inversion work (Tweet). Further, they do not provide the code.

Code

The authors not only open-source the code to fine-tune the model; they also provide the code to create the library vec2text. The following are the most important code snippet of this work (vec2text/vex2text/trainers/corrector).

model: The inverter model that maps embeddings back to text.

def invert_embeddings(

embeddings: torch.Tensor,

corrector: vec2text.trainers.Corrector,

num_steps: int = None,

sequence_beam_width: int = 0,

) -> List[str]:

corrector.inversion_trainer.model.eval()

corrector.model.eval()

gen_kwargs = copy.copy(corrector.gen_kwargs)

gen_kwargs["min_length"] = 1

gen_kwargs["max_length"] = 128

if num_steps is None:

assert (

sequence_beam_width == 0

), "can't set a nonzero beam width without multiple steps"

regenerated = corrector.inversion_trainer.generate(

inputs={

"frozen_embeddings": embeddings,

},

generation_kwargs=gen_kwargs,

)

else:

corrector.return_best_hypothesis = sequence_beam_width > 0

regenerated = corrector.generate(

inputs={

"frozen_embeddings": embeddings,

},

generation_kwargs=gen_kwargs,

num_recursive_steps=num_steps,

sequence_beam_width=sequence_beam_width,

)

output_strings = corrector.tokenizer.batch_decode(

regenerated, skip_special_tokens=True

)

return output_strings

class Corrector(BaseTrainer):

def __init__(

self,

model: CorrectorEncoderModel,

inversion_trainer: InversionTrainer,

args: Optional[TrainingArguments],

**kwargs,

):

// ...

def generate(

self,

inputs: Dict,

generation_kwargs: Dict,

num_recursive_steps: int = None,

sequence_beam_width: int = None,

) -> torch.Tensor:

//...

while num_recursive_steps >= 1:

gen_text_ids, hypothesis_embedding, best_scores = self._generate_with_beam(

inputs=inputs,

generation_kwargs=generation_kwargs,

num_recursive_steps=num_recursive_steps,

num_recursive_steps_so_far=num_recursive_steps_so_far,

sequence_beam_width=sequence_beam_width,

)

inputs["hypothesis_input_ids"] = gen_text_ids

inputs["hypothesis_attention_mask"] = (

gen_text_ids != self.model.encoder_decoder.config.pad_token_id

).int()

inputs["hypothesis_embedding"] = hypothesis_embedding

# step counters

num_recursive_steps -= 1

num_recursive_steps_so_far += 1

// ...

def _generate_with_beam(

self,

inputs: Dict,

generation_kwargs: Dict,

num_recursive_steps: int,

num_recursive_steps_so_far: int,

sequence_beam_width: int,

) -> Tuple[torch.Tensor, torch.Tensor, torch.Tensor]:

// ...

if (num_recursive_steps_so_far == 0) and (

self.initial_hypothesis_str is not None

):

//...

else:

outputs = self.model.generate(

inputs=inputs,

generation_kwargs=generation_kwargs,

return_dict_in_generate=True,

)

gen_text_ids = outputs.sequences

// ...

Minimal Working Example

The provided library is very easy-to-use. The following is a minimal working example:

import os

import torch

import vec2text

from langchain.embeddings import OpenAIEmbeddings

embedding_model = OpenAIEmbeddings(

openai_api_key=os.getenv("OPENAI_API_KEY")

)

query = "What is your favoriate opera?"

positives = [

"I love Lucia di Lammermoor because Luica's powerful presence is really inspiring.",

"Le Nozze di Figaro is my favorite because of the fun plot and timeless Mozart music.",

]

negatives = [

"I love pepperoni pizza",

"Cancun is my favoriate holiday destination."

]

query_embedding = embedding_model.embed_query(query)

positive_embeddings = embedding_model.embed_documents(positives)

negative_embeddings = embedding_model.embed_documents(negatives)

corrector = vec2text.load_corrector("text-embedding-ada-002")

inverted_positives = vec2text.invert_embeddings(

embeddings=torch.tensor(positive_embeddings).cuda(),

corrector=corrector

)

Anatomy

Additional Notes

-

This idea could generalize to prompt search as prompt engineering could be seen as a more general form of query refinement to better elicit the knowledge from an LLM. However, the difference is that we often do not have desired output; this makes the search for the prompts difficult. Eventually, the idea could work for prompt engineering only when we have at least one ideal output.

The Dynasour system from UCLA is one such attempt: they are trying to create instruction tuning data from regular HuggingFace datasets; these HuggingFace datasets do not come with instructions.

- The paper [2] shows a novel way of manipulating embeddings – using Seq2Seq model’s decoder only. This is not previously possible for encoder-only, encoder-decoder, or decoder-only models.

-

Gradients provide more information than embeddings, as is noted by [4].

However, such techniques do not apply to textual inversion: the gradient of the model is relatively high-resolution; we consider the more difficult problem of recovering the full input text given only a single dense embedding vector.

- In the embedding space, two embeddings could collide even though they have no token overlap [7].

-

RTT is an useful way to add perturbations to the inputs; another way worth trying is denoising [9], which turns out to be less effective than RTT. Further, the choice of language in RTT is important. For example, the paper [8] chooses German as the pivot due to more word reorderings.

As explained by Shen et al. (2020), the intuition behind using denoising with auto-encoders is that the noise constraints the auto-encoder to put similar sentences (in terms of the denoising objective) next to each other in the latent space. However, the problem with denoising is that it maps together sentences that are close in edit distance but may have completely different meanings.

Reference

-

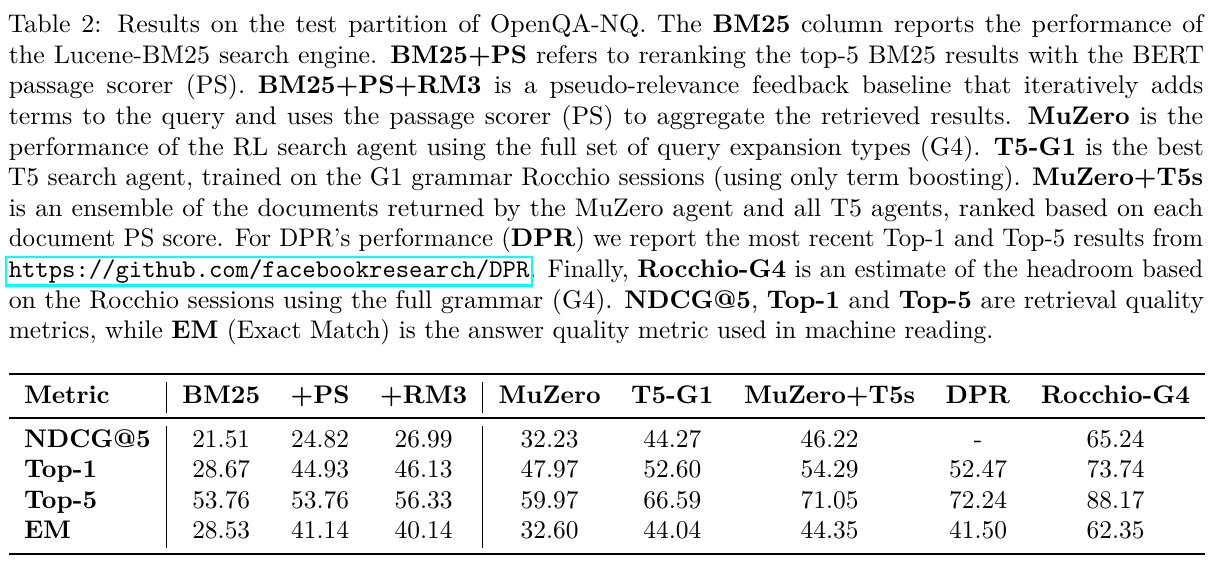

[2109.00527] Boosting Search Engines with Interactive Agents (Adolphs et al., TMLR 2022): This is a feasibility study of an emsemble of BM25 plus an interpretable reranking scheme to work on par DPR on the

natural_questionsdataset; this is consistent with DPR in its evaluation. The main advantage is intepretability rather than performance.

- Decoding a Neural Retriever’s Latent Space for Query Suggestion (Adolphs et al., EMNLP 2022)

- What Are You Token About? Dense Retrieval as Distributions Over the Vocabulary (Ram et al., ACL 2023): This paper proposes a method to project embeddings onto the vocabulary and obtains a distribution over the tokens. The motivation for this paper is interpretability.

- [2310.06816] Text Embeddings Reveal (Almost) As Much As Text (Morris et al., EMNLP 2023)

- Large Dual Encoders Are Generalizable Retrievers (Ni et al., EMNLP 2022): This paper proposes the Generalization T5 dense Retrievers (GTR) model that many papers build their solutions upon.

- PAQ: 65 Million Probably-Asked Questions and What You Can Do With Them (Lewis et al., TACL 2021)

- Adversarial Semantic Collisions (Song et al., EMNLP 2020)

- [2209.06792] vec2text with Round-Trip Translations (Cideron et al. from Google Brain)

- [1905.12777] Educating Text Autoencoders: Latent Representation Guidance via Denoising (Shen et al., ICML 2020)