Overview

This set of evaluation metrics I discuss in this post is organized based on the typical tasks in NLP (see [1]); they are:

- Sequence Classification

- Token Classification (Tagging)

- Generation: This category includes all tasks whose outputs are a sequence of tokens. For example, question answering, machine translation, text summarization and text simplification, and paraphrasing.

- Retrieval

- Regression

There is also a section dedicated to basic statistics, such as correlations, confidence intervals, and p-values.

Basic Statistics

Correlation

Sequence Classification

Confusion Matrix

The \mathbf{C}_{ij} means the number of samples of class i receive the prediction j; the rows are the true classes while the columns are the predictions.

| Notation |

Formula |

| $\mathrm{TNR}$ |

$\frac{\mathrm{TN}}{\mathrm{N}}$ |

| $\mathrm{FNR}$ |

$\frac{\mathrm{FN}}{\mathrm{N}}$ |

| $\mathrm{FPR}$ |

$\frac{\mathrm{FP}}{\mathrm{P}}$ |

| $\mathrm{TPR}$ |

$\frac{\mathrm{TP}}{\mathrm{P}}$ |

| $P$ |

$\frac{\mathrm{TP}}{\mathrm{TP}+\mathrm{FP}}$ |

| $R$ |

$\frac{\mathrm{TP}}{\mathrm{TP}+\mathrm{FN}}$ |

import numpy as np

from sklearn.metrics import confusion_matrix

y_true = np.array([1, 0, 1, 0, 1])

y_pred = np.array([1, 0, 1, 1, 0])

# raw counts

tn, fp, fn, tp = confusion_matrix(

y_true=y_true,

y_pred=y_pred

).ravel()

print(tn, fp, fn, tp)

# expected output: (1, 1, 1, 2)

# actual output: array([1, 1, 1, 2])

# tnr, fpr, fnr, tpr

tnr, fpr, fnr, tpr = confusion_matrix(

y_true=y_true,

y_pred=y_pred,

normalize="true",

).ravel()

print(tnr, fpr, fnr, tpr)

# expected output: (1/2, 1/2, 1/3, 2/3)

# actual output: 0.5 0.5 0.3333333333333333 0.6666666666666666

- We could use the code below to visualize a confusion matrix. Following the example above, we have:

import pandas as pd

df = pd.DataFrame(

confusion_matrix(y_true, y_pred),

index=labels

columns=labels,

)

sns.plot(df)

Matthews Correlation Coefficient (MCC)

The Matthews Correlation Coefficient (MCC) (also called \phi statistic) is a special case of Pearson’s correlation for two boolean distributions with value {-1, 1}.

The range of MCC is [-1, 1], where 1 – perfect predictions, 0 – random prediction, and -1 – inverse prediction. It is better than F1 score (and therefore accuracy) as it does not have similar majority-class bias by additionally considering TN (remember that P=\frac{TP}{TP+FP}, R=\frac{TP}{TP+FN}, and F1=\frac{2PR}{P+R}=\frac{2TP}{2TP+FP+FN} and TN is not considered in F1).

Concretely, consider the following examples

- Example 1: Consider a dataset with 10 samples and y =(1, 1, \cdots, 1, 0) and \hat{y} = (1, 1, \cdots , 1, 1), then the F1=0.9474, MCC=0.

- Example 2: Consider the use case A1 detailed in [3], given a dataset of 91 positive samples and 9 negative samples, suppose all 9 negative samples are misclassified and 1 positive sample is misclassified (i.e. TP=90, TN=0, FP=9, FN=1), then F1=0.95 while MCC=-0.03.

A potential issue when computing the MCC is that the metric is undefined when y is all 0 or all 1, and this will make either TP or TN undefined.

This issue also come with F1 score as it could be written as F1=\frac{2P\cdot R}{P+R}=\frac{2TP}{2TP+FP+FN} and it could not be computed when TP is undefined when all labels are 0.

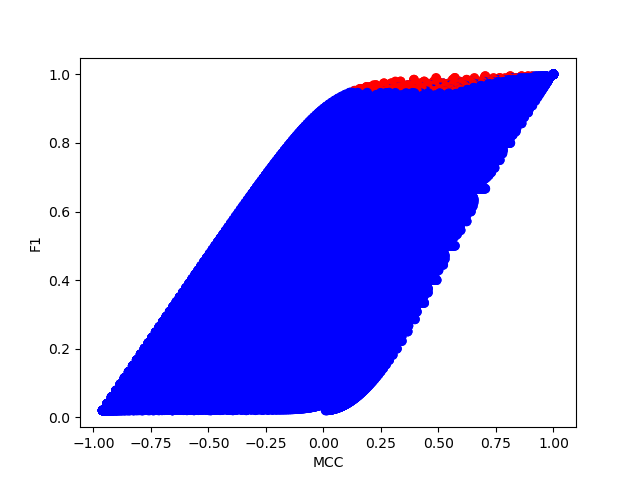

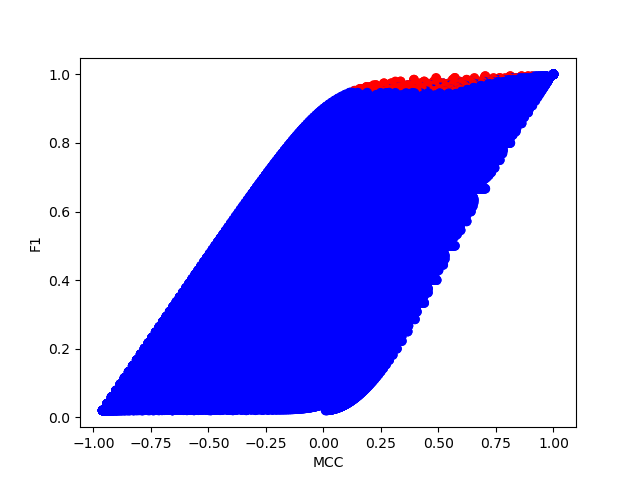

To have a better comparison between MCC and F1, consider a dataset with 100 samples, plot the F1 \sim MCC curve given different combinations of TP, FP, TN and FN using simulation. The dots colored red are those (1) achieve an more than 95% F1 score, and (2) correspond to a dataset where there are more than 95% positive samples. We could see that their MCC is relatively low.

Ranking

Typical ranking metrics include Mean Reciprocal Rank, Mean Average Precision, Precision, and Normalized Discounted Cumulative Gain (NDCG).NDCG is more comprehensive than other metrics as it considers the location of relevant items.

| Metric |

Formula |

Note |

| MRR |

$\frac{1}{N} \sum _ {i=1}^N \frac{1}{r _ i}$ |

$r$ is the first relevant item for each query. |

| MAP@k |

$\frac{1}{N} \sum _ {i=1}^N \mathrm{AP}@k(i)$ |

$\mathrm{AP}@k(i) = \frac{1}{\text{# Relevant Items in Top-}k} \sum _ {i=1} ^ k \mathrm{P}@k(i) \cdot 1(i\ \text{is relevant})$. |

| P@k |

$\frac{1}{N} \sum _ {i=1}^N \mathrm{P}@k(i)$ |

$\mathrm{P}@k(i)$ is the ratio of relevant items in the total $k$ items for query $i$. |

| NDCG@k |

$\frac{\mathrm{DCG}@k}{\mathrm{IDCG}$k}$ |

$\mathrm{DCG}@k=\sum _ {i=1} ^ k \frac{\mathrm{rel} _ i}{\log _ 2 (i+1)}$, $\mathrm{IDCG}@k$ is the $\mathrm{DCG}@k$ for the ranking list of ideal order. |

Suppose there are two queries q1 and q2, the returned documents have the following relevance list (1 as relevant and 0 as irrelevant):

q1 = [1, 0, 1, 0, 1]

q2 = [0, 0, 1, 1, 0]

Then we have the following results:

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

AP@5 |

DCG@5 |

IDCG@5 |

| P@k for q_1 |

1 |

1/2 |

2/3 |

1/2 |

3/5 |

$\frac{1}{3}\times (1 + \frac{2}{3} + \frac{3}{5}) = 0.756$ |

$1 + \frac{1}{\log _ 2 4}+\frac{1}{\log_2 6}$ |

$1+\frac{1}{\log _ 2 3}+\frac{1}{\log _ 2 4}$ |

| P@k for q_2 |

0 |

0 |

1/3 |

1/2 |

2/5 |

$\frac{1}{2}\times (\frac{1}{3} + \frac{1}{2})=0.417$ |

$\frac{1}{\log _ 2 4}+\frac{1}{\log_2 5}$ |

$1+\frac{1}{\log _ 2 3}$ |

Then, we have

- P@5: \frac{1}{2} \times (\frac{3}{5} + \frac{2}{5}) = 0.5.

- MAP@5: \frac{1}{2} \times (0.756 + 0.417)=0.587

Reference

- [2107.13586] Pre-train, Prompt, and Predict: A Systematic Survey of Prompting Methods in Natural Language Processing: This survey gives clear categories of NLP tasks:

GEN , CLS, and TAG.

- Confusion matrix – Wikipedia: A comprehensive overview of a list of related metrics.

- The advantages of the Matthews correlation coefficient (MCC) over F1 score and accuracy in binary classification evaluation | BMC Genomics | Full Text (Chicco and Jurman).

- Calculate Pearson Correlation Confidence Interval in Python | Zhiya Zuo: The author writes a function that outputs Pearson correlation, p-value, and confidence intervals.

- sample size – Pearson correlation minimum number of pairs – Cross Validated