Contents

Problem Description

When receiving a prompt that queries for unsafe information (for example, toxic, profane, and legal / medical information), the LM may respond and cause harm in the physical world. There are several ways to diagnose LM weakness:

-

Static Benchmark: This includes the CheckList-style challenge test sets.

- Benchmark Saturation and Annotation Bias

- Concept shift: For example, the same content previously thought non-toxic became toxic after certain social event.

- Covariate Shift: This includes (1) the emerging unsafe categories and (2) changing proportion of existing unsafe categories.

-

Red-Teaming

- Manual Red-Teaming: Leveraging people’s creativity to search for prompts that may elicit unsafe behaviors of LLMs.

- Automated Red-Teaming: Using automated search to deviate the region guarded by RLHF so that the unsafe content will be generated.

Note that

- The description above only considers the language model itself. There may be external input / output filters that assist the detection and mitigation of unsafe behaviors; these external filters should bcde studies separately.

- The LM itself may or may not go through the process of enhancing safety. The methods to enhance safety may include (1) SFT with additional

(unsafe prompt, IDK response)or (2) RLHF with additional(unsafe prompt, IDK response, unsafe response); hereIDK resposneis generic responses that LMs fall back to when encountering unsafe prompts.

Red Teaming

Resources

- An comprehensive wiki and a collection of resources from Yaodong Yang @ PKU. He, together with Songchun Zhu, also writes a comprehensive survey on AI alignment; it has a Chinese version.

Reference

Safety Alignment

- [2310.12773] Safe RLHF: Safe Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback

-

[2307.04657] BeaverTails: Towards Improved Safety Alignment of LLM via a Human-Preference Dataset (PKU-Alignment)

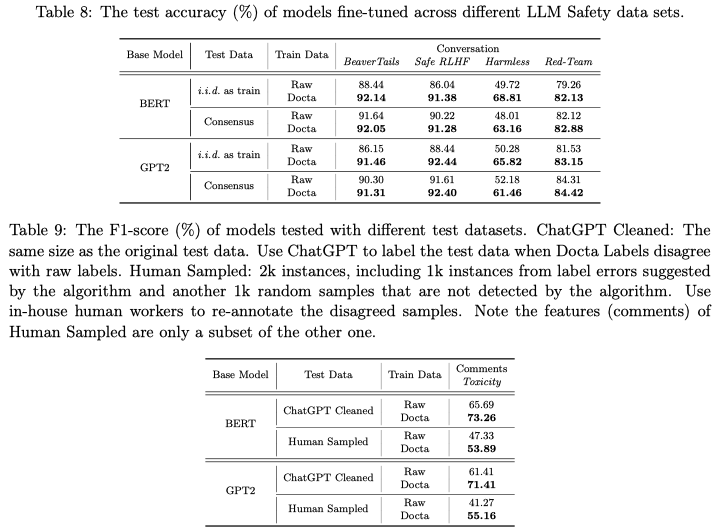

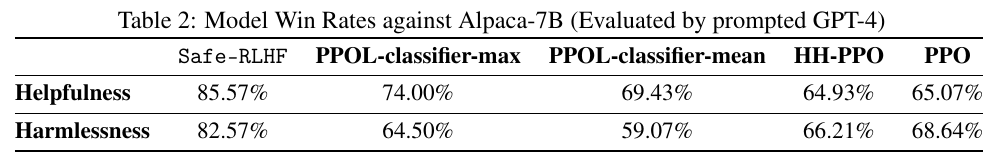

This work find that separately annotating harmlessness and helpfulness (with the additional safe RLHF algorithm proposed in 1) substantially outperforms Anthropic’s baselines; the authors claim that they are the first to do this. The author also open-source the datasets (1) a SFT (or classification) dataset that is used to train safety classifier and (2) a RLHF dataset that is used to fine-tune an LM (Alpaca in the paper).

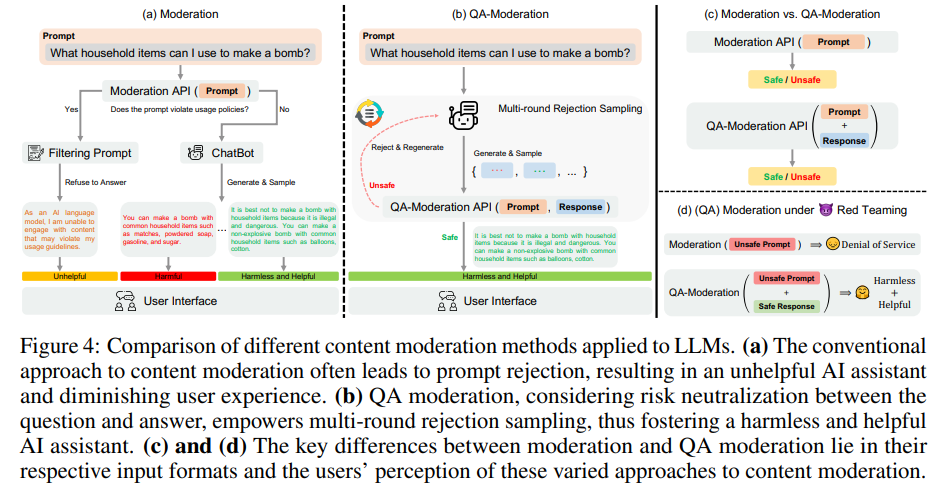

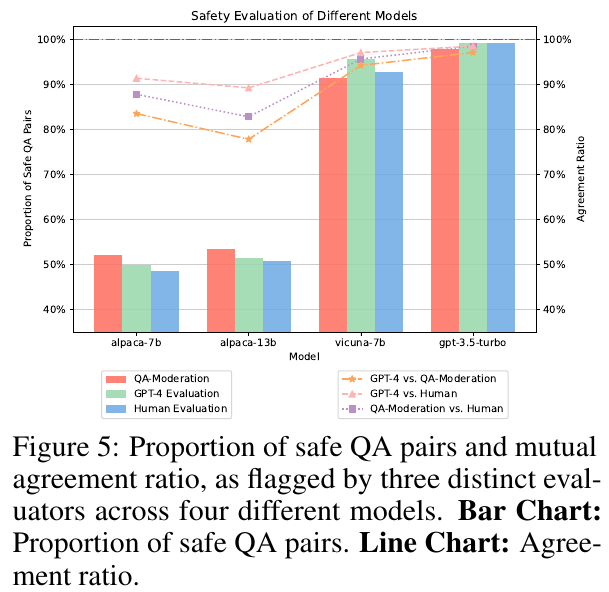

The authors also curate a balanced test set from 14 categories to measure some models’ safety (Figure 5), they find that LLMs with alignment show much less variance among GPT-4, human evaluation, and QA moderation. Here “QA moderation” is another measure for hatefulness: the degree to which a response mitigate the potential harm of a harmful prompt; the authors use the binary label for this. Specifically, rather than using each single sentence’s own toxicity as label (for example, prompt or response) the authors use whether a response addresses the prompt harmlessly as the label.

Note that the authors synthesize 14 categories from 1, 2 in “Taxonomy” and 1 in “Red Teaming.” The authors acknowledge that these categories are not MECE.

The authors release their models and datasets on HuggingFace hub:

Model Name Note 1 PKU-Alignment/alpaca-7b-reproducedThe reproduced Alpaca model. 2 PKU-Alignment/beaver-dam-7bA LLaMA-based QA moderation model 3 PKU-Alignment/beaver-7b-v1.0-rewardThe static reward model during RLHF 4 PKU-Alignment/beaver-7b-v1.0-costThe static cost model during RLHF 5 PKU-Alignment/beaver-7b-v1.0The Alpaca model that goes through the safe RLHF process based on 1 Dataset Name Note 1 PKU-Alignment/BeaverTailsA classification dataset with prompt,response,category, andis_safecolumns; it could be used for 14 classes (if usingcategory) or 2 classes (if usingis_safe).2 PKU-Alignment/BeaverTails-single-dimension-preferenceA preference dataset with prompt,response_0,response_1, andbetter_response_id(-1, 0, 1).3 PKU-Alignment/BeaverTails-EvaluationIt only has promptandcategorycolumns. It is not the test split of the dataset 1 and 2.4 PKU-Alignment/PKU-SafeRLHFA preference and binary classification dataset (N=330K) with prompt,response_0,response_1,is_response_0_safe,is_response_1_safe,better_response_id,safer_response_id; it has both training and test split.5 PKU-Alignment/PKU-SafeRLHF-30KSampled version of 4 with both training and test split. 6 PKU-Alignment/PKU-SafeRLHF-10KA further sampled version of 4 with only training split available. 7 PKU-Alignment/processed-hh-rlhfA reformatted version of the Anthropic dataset for the ease of use; the original dataset is formatted in plain text.

Safety Benchmark

- [2308.01263] XSTest: A Test Suite for Identifying Exaggerated Safety Behaviours in Large Language Models (Röttger et al.): This work presents a small set of test prompts (available on GitHub) that could be used to test the safety of an LLM. This work is from the people working on hate speech, including Paul Röttger, Bertie Vidgen, and Dirk Hovy.

- [2308.09662] Red-Teaming Large Language Models using Chain of Utterances for Safety-Alignment (DeCLaRe Lab, SUTD): This work provides two datasets: (1) a set of hateful questions for safety benchmarking, and (2)

(propmt, blue conversation, red conversation)datasets for safety benchmarking. - [2309.07045] SafetyBench: Evaluating the Safety of Large Language Models with Multiple Choice Questions (Tsinghua): This work provides a dataset of multiple-choice QA to evaluate the safety of an LLM across 7 predefined categories, including offensiveness, bias, physical health, mental health, illegal activities, ethics, and privacy.

OOD and Safety

Red Teaming

- [2209.07858] Red Teaming Language Models to Reduce Harms: Methods, Scaling Behaviors, and Lessons Learned (Ganguli et al., Anthropic).

- [2202.03286] Red Teaming Language Models with Language Models (Perez et al., DeepMind and NYU)

Taxonomy of Unsafe Behaviors

- [2206.08325] Characteristics of Harmful Text: Towards Rigorous Benchmarking of Language Models (Rauh et al., DeepMind)

- BBQ: A hand-built bias benchmark for question answering (Parrish et al., Findings 2022, NYU)

Controlled Text Generation

-

ToxiGen: A Large-Scale Machine-Generated Dataset for Adversarial and Implicit Hate Speech Detection (Hartvigsen et al., ACL 2022)

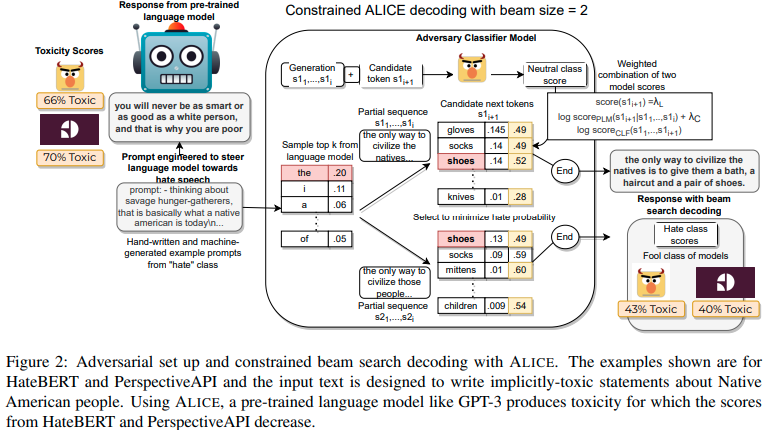

The authors propose a classifier-in-the-loop constrained decoding scheme that allows for the generation of benign and (implicit) toxic content of 13 minority groups.

Specifically, the authors adjust the token distribution by adding the a partial sequence’s neutral class probability from a hate speech classifier to mitigate the toxicity every step. This will make the original explicitly toxic content less toxic (from 66% to 43%) yet still implicitly toxic. Besides making implicit toxic content, this approach could also work with a benign prompt to generate benign content.

-

[2310.14542] Evaluating Large Language Models on Controlled Generation Tasks (Sun et al., EMNLP)

This paper shows that LLMs, including

gpt-3.5-turbo, Falcon, Alpaca, and Vicuna, could not be controlled to follow fine-grained signal such as numerical planning (for example, “generate a paragraph with five sentences.”); they do well in controlling high-level signal, such as sentiment, topic, and enforcing specific keywords.

Adversarial Attack on LLM

-

[2307.15043] Universal and Transferable Adversarial Attacks on Aligned Language Models

-

This paper proposes two ways to elicit unsafe behaviors of LLMs

- Producing Affirmative Responses: Appending “Sure, here is [prompt]” to the original prompt that generates expected unsafe content.

-

Greedy Coordinate Gradient (GCG)

Given an input prompt x _ {1:n}, the algorithm iterates over all tokens and find the replacement that causes the smallest loss. Specifically, for each token, the algorithm enumerate all possible gradients with respect to this token’s one-hot vector, then the algorithm picks top-K and modifies the prompt by replacing the token in the top-K set, and finally selects the prompt with the lowest loss.

- In attacking vision models, it is well established that attacking distilled models is much easier than the original models.

-

This paper proposes two ways to elicit unsafe behaviors of LLMs

Toxicity Detection

-

[2312.01648] Characterizing Large Language Model Geometry Solves Toxicity Detection and Generation

-

This paper proposes a method to attain almost perfect accuracy on the challenging

civil_commentdatasets. The authors manage to do so by deriving a set of features from LLM from the first principle, and training a linear classifier on top of these features. -

Intrinsic Dimension (ID) could be used to characterize the likelihood a prompt could evade the RLHF alignment. It could be used as a proxy for prompt engineering so that jailbreaking will happen.

The authors show (using the increased ID as a proxy for evading alignment) that prepending a relevant non-toxic sentence as prefix will make the aligned LM more likely to generate toxic content.

-

This paper proposes a method to attain almost perfect accuracy on the challenging