[Semantic Scholar] – [Code] – [Tweet] – [Video] – [Website] – [Slide] – [Leaderboard]

Change Logs:

- 2023-09-06: First draft. The paper provides a standardized package for many domain generalization algorithms, including group DRO, DANN, and Coral.

Background

Distribution shifts happen when test conditions are “newer” or “smaller” compared to training conditions. The paper defines them as

-

Newer: Domain Generalization

The test distribution is related to but distinct (aka. new or unseen during training) to the training distributions. Note that the test conditions are not necessarily a superset of the training conditions; they are not “larger” compared to the “smaller” case described below.

Here are two typical examples of domain generalization described in the paper:

- Training a model based on patient information from some hospitals and expect the model to generalize to many more hospitals; these hospitals may or may not be a superset of the hospitals we collect training data from.

- Training an animal recognition model on images taken from some existing cameras and expect the model to work on images taken on the newer cameras.

-

Smaller: Subpopulation Shift

The test distribution is a subpopulation of the training distributions. For example, degraded facial recognition accuracy on the underrepresented demographic groups ([3] and [4]).

Evaluation

The goal of OOD generalization is training a model on data sampled from training distribution P^\text{train} that performs well on the test distribution P^\text{test}. Note that as we could not assume the data from two distributions are equally difficult to learn, the most ideal case is to at least train two models (or even more ideally three models) and take 2 (or 3) measurements:

| Index |

Goal |

Training Data |

Testing Data |

| 1 |

Measuring OOD Generalization |

$D ^ \text{train} \sim P^ \text{train}$ |

$D ^ \text{test} \sim P^ \text{test}$ |

| 2 |

Ruling Out Confounding Factor of Distribution Difficulty |

$D ^ \text{test} _ \text{heldout} \sim P^ \text{test}$ |

$D ^ \text{test} \sim P^ \text{test}$ |

| 3 |

(Optional) Sanity Check |

$D ^ \text{train} \sim P^ \text{train}$ |

$D ^ \text{train} _ \text{heldout} \sim P^ \text{train}$ |

However, the generally small test sets make the measurement 2 hard or even impossible: we could not find an additional held-out set D ^ \text{test} _ \text{heldout} that matches the size of D ^ \text{train} to train a model.

The authors therefore define 4 relaxed settings:

| Index |

Setting |

Training Data |

Testing Data |

| 1 |

Mixed-to-Test |

Mixture of P^ \text{train} and P^ \text{test} |

$P^ \text{train}$ |

| 2 |

Train-to-Train (aka. setting 3 above) |

$P^ \text{train}$ |

$P^ \text{train}$ |

| 3 |

Average. This is a special case of 2; it is only suitable for subpopulation shift, such as Amazon Reviews and CivilComments. |

Average Performance |

Worst-Group Performance |

| 4 |

Random Split. This setting destroys the P ^ \text{test}. |

$\tilde{D} ^ \text{train} := \mathrm{Sample}(D ^ \text{train} \cup D ^ \text{test})$ |

$(D ^ \text{train} \cup D ^ \text{test}) \backslash \tilde{D} ^ \text{train}$ |

Dataset

The dataset includes regular and medical image, graph, and text datasets; 3 out of 10 are text datasets, where the less familiar Py150 is a code completion dataset. Note that the authors fail to cleanly define why there are subpopulation shifts for Amazon Reviews and Py150 datasets as the authors acknowledge below:

However, it is not always possible to cleanly define a problem as one or the other; for example, a test domain might be present in the training set but at a very low frequency.

For Amazon Reviews dataset, one viable explanation on why there is subpopulation shift is uneven distribution of reviews on the same product in the train, validation, and test set.

| Name |

Domain Generalization |

Subpopulation Shift |

Notes |

| CivilComments |

No; this is because the demographic information of the writers are unknown; if such information is known, we could also create a version with domain generation concern. |

Yes; this is because the mentions of 8 target demographic groups are available. |

The only dataset with only subpopulation shift. |

| Amazon Reviews |

Yes; due to disjoint users in the train, OOD validation, and OOD test set; there are also ID validation and ID test set from same users as the training set. |

Yes |

|

| Py150 |

Yes; due to disjoint repositories in train, OOD validation, and OOD test set; there are also ID validation and ID test set from same repositories as the training set. |

Yes |

|

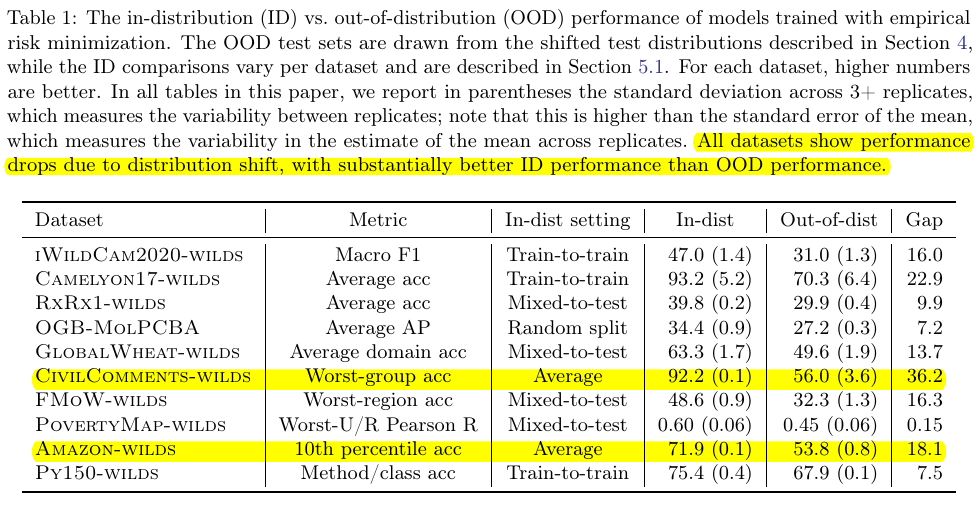

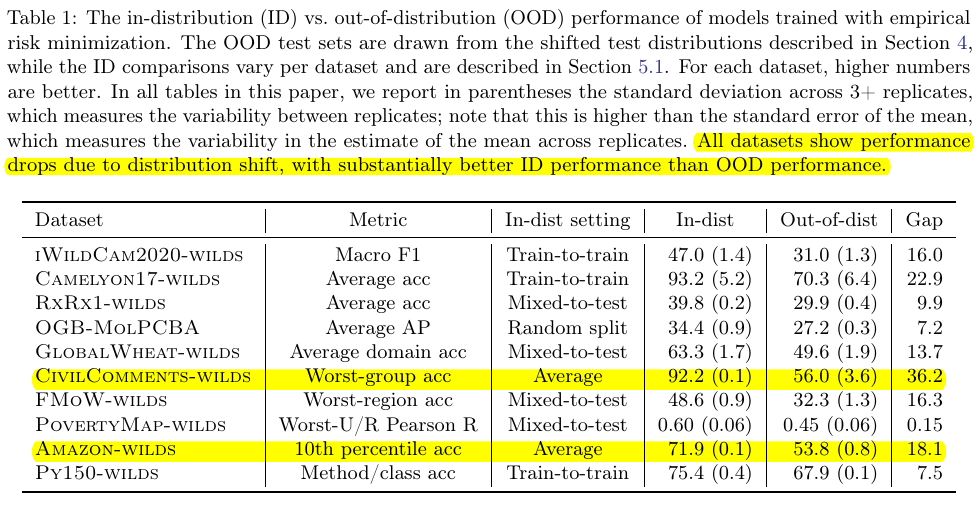

Importantly, the authors note that performance drop is a necessary condition of distribution shifts. That is

-

The presence of distribution shifts do not lead to performance drop on the test set.

-

If we observe degraded test set performance, then there might be distribution shifts (either domain generalization or subpopulation shift). Here are two examples:

-

Time Shift in Amazon Review Dataset: The model trained on 2000 – 2013 datasets perform similarly well (with 1.1% difference in F1) as the model trained on 2014 – 2018 datasets on the test set sampled from 2014 – 2018.

-

Time and User Shift in Yelp Dataset: For the time shift, the setting is similar as Amazon Reviews; the authors observe a maximum of 3.1% difference. For the user shift, whether the data splits are disjoint in terms of users only influence the scores very little.

Experiments

Here is a summary of the authors’ experiments. Note that Yelp is not the part of the official dataset because it shows no evidence for distribution shift.

| Index |

Dataset |

Shift |

Existence |

| 1 |

Amazon Reviews |

Time |

No |

| 2 |

Amazon Reviews |

Category |

Maybe |

| 3 |

CivilComments |

Subpopulation |

Yes |

| 4 |

Yelp |

Time |

No |

| 5 |

Yelp |

User |

No |

Amazon Reviews

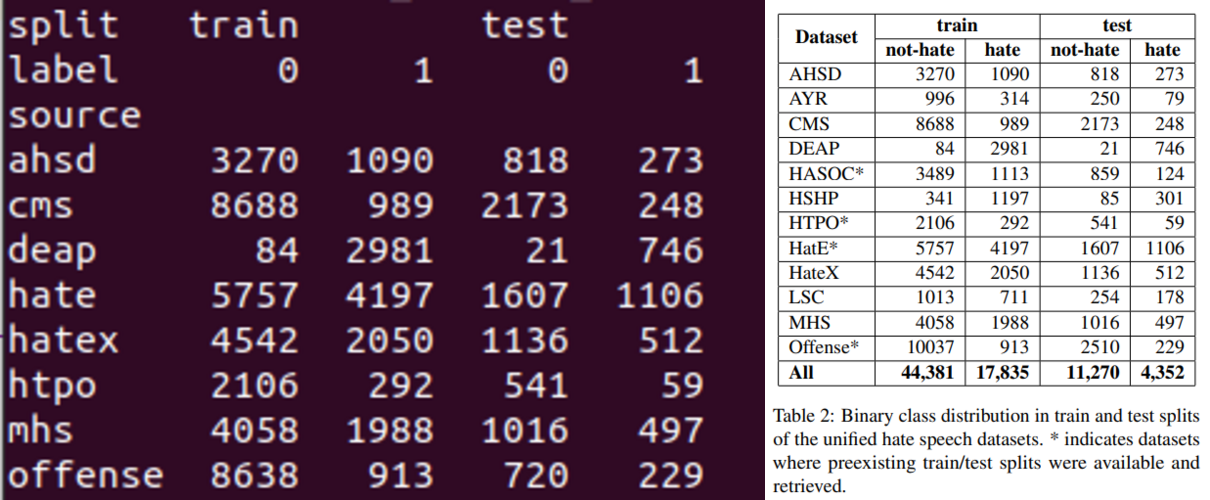

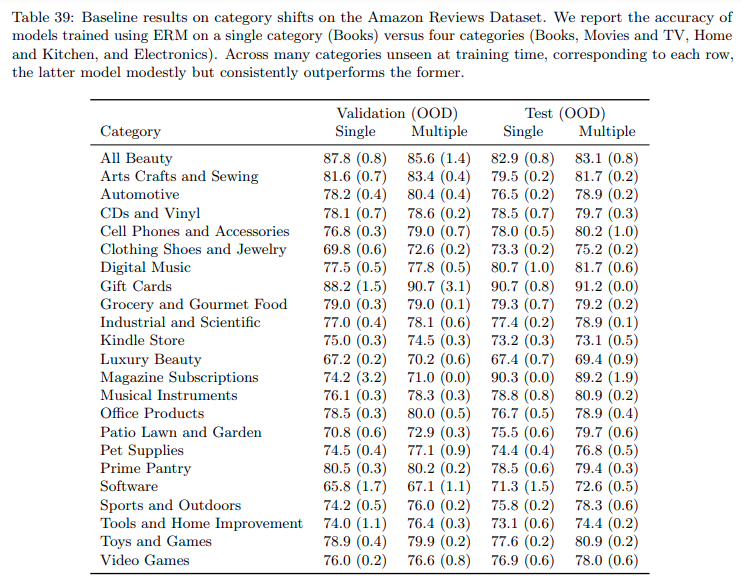

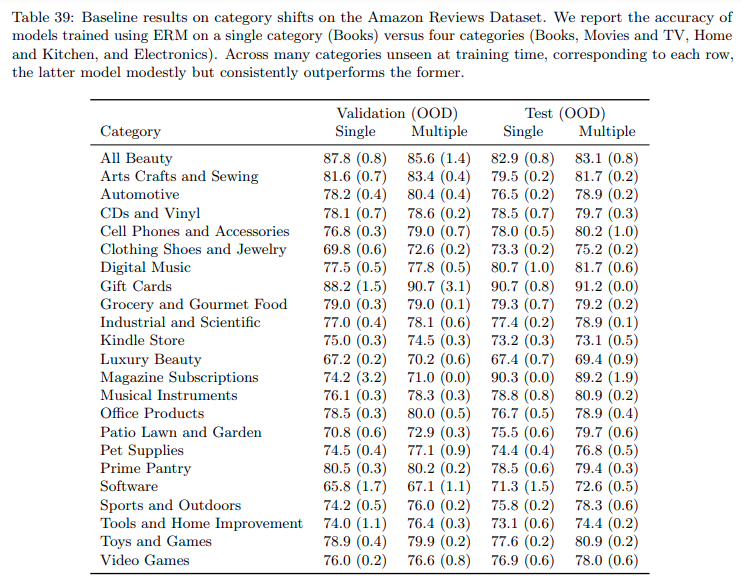

The authors train a model on one category (“Single”) and four categories (“Multiple”, “Multiple” is a superset of “Single”) and measure the test accuracy on other 23 disjoint categories.

The authors find that (1) training with more categories modestly yet consistently improves the scores, (2) the OOD category (for example, “All Beauty”) could have an even higher score than the ID categories, (3) the authors do not see strong evidence of domain shift as they could not rule out other confounding factors. Note that the authors here use the very vague term “intrinsic difficulty” to gloss over something they could not explain well.

While the accuracies on some unseen categories are lower than the train-to-train in-distribution accuracy, it is unclear whether the performance gaps stem from the distribution shift or differences in intrinsic difficulty across categories; in fact, the accuracy is higher on many unseen categories (e.g., All Beauty) than on the in-distribution categories, illustrating the importance of accounting for intrinsic difficulty.

To control for intrinsic difficulty, we ran a test-to-test comparison on each target category. We controlled for the number of training reviews to the extent possible; the standard model is trained on 1 million reviews in the official split, and each test-to-test model is trained on 1 million reviews or less, as limited by the number of reviews per category. We observed performance drops on some categories, for example on Clothing, Shoes, and Jewelry (83.0% in the test-to-test setting versus 75.2% in the official setting trained on the four different categories) and on Pet Supplies (78.8% to 76.8%). However, on the remaining categories, we observed more modest performance gaps, if at all. While we thus found no evidence for significance performance drops for many categories, these results do not rule out such drops either: one confounding factor is that some of the oracle models are trained on significantly smaller training sets and therefore underestimate the in-distribution performance.

The authors also control the size consistent for “Single” and “Multiple” settings. They show that training data with more domains (with increased diversity) is beneficial for improving OOD accuracies.

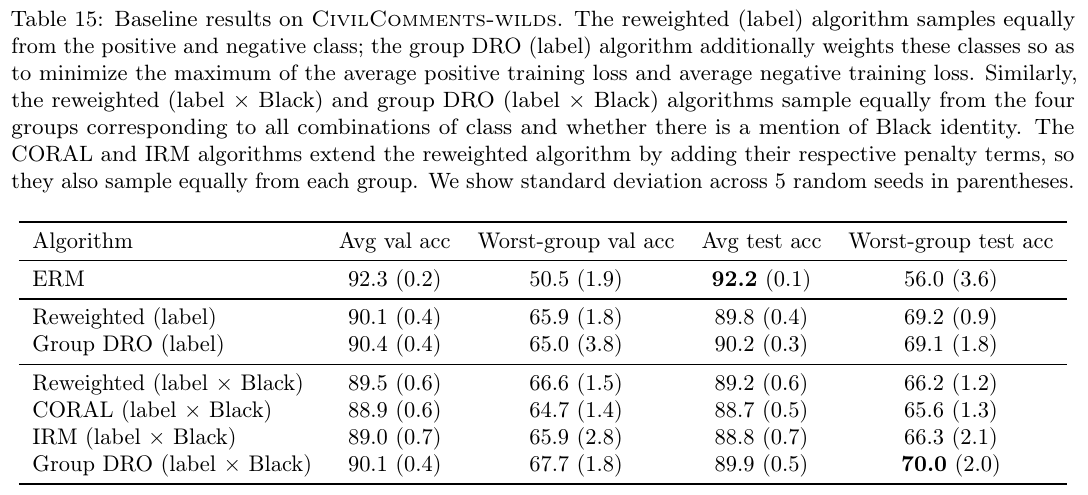

CivilComments

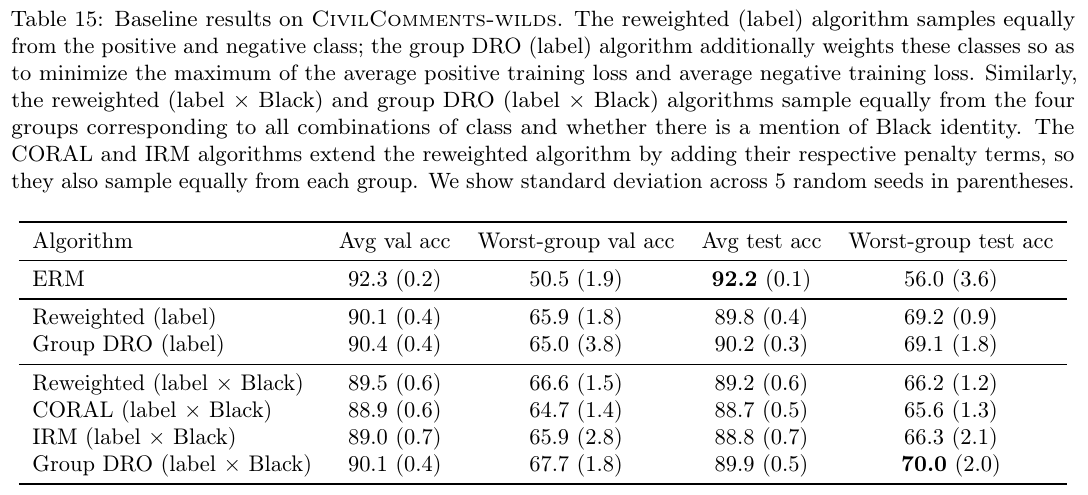

Each sample in the dataset has a piece of text, 1 binary toxicity labels, and 8 target labels (each text could include zero, one, or more identities). The authors use 8 TPR and TNR values to measure the performance (totaling 16 numbers).

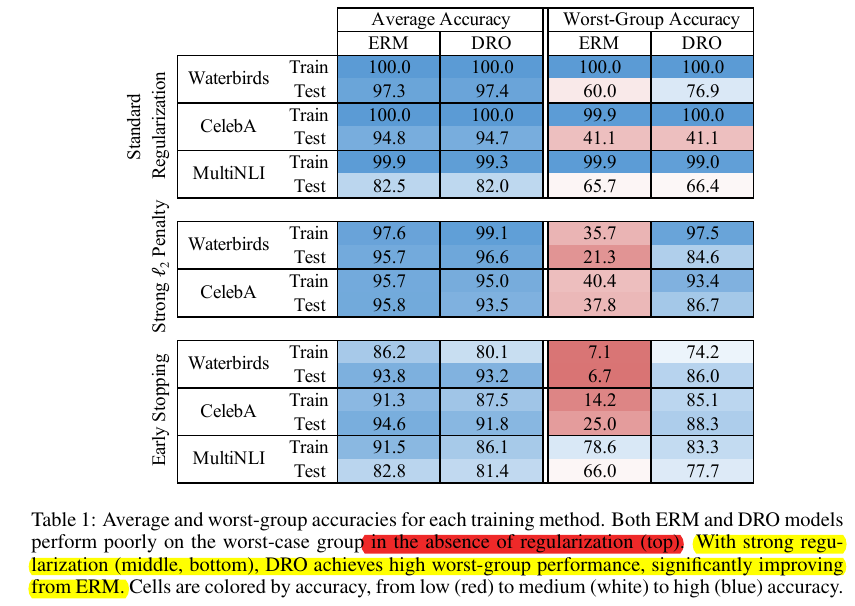

The authors observe subpopulation shifts: despite 92.2% average accuracy, the worst number among 16 numbers is merely 57.4%. A comparison of 4 mitigation methods shows that (1) the group DRO has the best performance, (2) the reweighting baseline is quite strong, the improved versions of reweighting (i.e., CORAL and IRM) are likely less useful.

In light of the effectiveness of the group DRO algorithm, the authors extend the number of groups to 2 ^ 9= 512, the resulting performance does not improve.

Additional Notes

-

Deciding Type of Distribution Shift

As long as there are no clearly disjoint train, validation, and test set as in Amazon Reviews and Py150 datasets, then there is no domain generalization issue; presence of a few unseen users in the validation or test set should not be considered as the domain generalization case.

-

Challenge Sets vs. Distribution Shifts

The CheckList-style challenge sets, such as HANS, PAWS, CheckList, and counterfactually-augmented datasets like [5], are intentionally created different from the training set.

Reference

- [2201.00299] Improving Out-of-Distribution Robustness via Selective Augmentation (Yao et al.): This paper proposes the LISA method that performs best on the Amazon dataset according to the leaderboard.

- [2104.09937] Gradient Matching for Domain Generalization (Shi et al.): This paper proposes the FISH method that performs best on the CivilComments dataset on the leaderboard.

- Gender Shades: Intersectional Accuracy Disparities in Commercial Gender Classification (Buolamwini and Gebru, FAccT ’18)

- Racial Disparities in Automated Speech Recognition (Koenecke et al., PNAS)

- [2010.02114] Explaining The Efficacy of Counterfactually Augmented Data (Kaushik et al., ICLR ’20)

- [2004.14444] The Effect of Natural Distribution Shift on Question Answering Models (Miller et al.): This paper trains 100+ QA models and tests them across different domains.

- Selective Question Answering under Domain Shift (Kamath et al., ACL 2020): This paper creates a test set of mixture of ID and OOD domains.