Contents

- 1 Overview

- 2 General Topics

- 3 Special Issues

- 3.1 Improving Machine Learning Models with Specifications

- 3.2 Reverse Engineering Queries Given Documents

- 3.3 Geometry of Embeddings and its Implication for Text Generation

- 3.4 Retrieval Augmented LM

- 3.5 HateModerate

- 3.6 Label Inconsistency of Different Datasets

- 3.7 Adversarial Attack on RLHF

- 3.8 OOD for Reward Model in RLHF

- 3.9 Applications of RLHF to Other Tasks

- 4 References

Overview

Here I document a list of general research questions that warrants searching, reading, thinking, and rethinking.

General Topics

Model Capacity

-

What is the broadly applicable measure of model capacity similar to a hardware performance benchmark that helps practitioners pick up the suitable model to start building their applications?

- Note: Model capacity mostly determines the performance upper bound of a model. The actual model performance may also related to how the model is trained with what set of hyperparameters.

- Hypothesis: A straightforward choice is the number of parameters a model has. However, one may question the correlation between the parameter count and this measure, i.e., the parameter count may need to be a valid proxy for the model capacity.

Generalization

-

Existence of Universal Generalization

Specifically, suppose there are K texts existing in the world at time t, and they are all labeled by an oracle; if we fine-tune a

bert-base-uncasedwith k \ll K samples as a classification model, is there any hope that this fine-tuned model perform reasonably well (needs more precise definition) on all (K-k) samples.- Experiment: We could only approximate the oracle by some knowingly most capable models like GPT-4. We therefore have two datasets, one from (a) original annotations and (b) the other from oracle (approximated by GPT-4) annotations. Could the model fine-tuned on dataset (b) generalize better than (a)?

- Question: Despite the generalization, could the fine-tuned model also inherit the bias (needs more precise definition) of GPT-4?

Text Classification, Annotation Bias, and Spurious Correlation

Does text classification work by relying on the spurious correlation (likely due to annotation bias where the annotators seek to take the shortcuts to complete their assigned tasks as soon as possible) between a limited number of words in the input text and output label? Therefore, is the better model indeed the model that better exploits the spurious correlation?

> - Hypothesis: If the K samples are all annotated by an oracle, then any *reasonably capable* model (needs more precise definition) can generalize well.

> - Tentative Experiment: If we replace the words in the list with their hypernyms, will the system performance drop?

Life Long and Continual Learning

Suppose we have a generalizable model at time t if we want the model to serve the users indefinitely. What are the strategies that make the model generalize well across time?

Data Distribution

In machine learning theory, we often encounter concepts such as “i.i.d.” Understanding “distribution” for tabular data is straightforward, where the list of variables forms a joint distribution that predicts the label y. However, what could be considered a “distribution” for texts is less clear. Note that this is possible for images, for example, modeling the gray-scale images as a Dirichlet multimodal distribution that predicts digits from 0 to 9.

Data Annotation

The labels in the NLP tasks have different levels of subjectivity. For example, the grammatical error correction is less subjective, sentiment classification is moderately subjective, and the topics like hate speech, suicidal ideation [1], and empathy [2] are either extremely subjective or requires expert knowledge.

The difficulty here it to mitigate the ambiguity during data annotation and make sure the information available in texts matches well with the label. Ideally, if we know the true underlying label of a text, we could fine-tune any reasonably capable model to generalize well.

Data Selection and Data Pruning for Classification Tasks

As of 2023-10-11, I have not seen a single work on the data selection for classification tasks; there are plenty of works on optimizing data mixture for language model pretraining. One likely reason why this happens is that the quality of classification datasets depends on both texts and labels; investigating the label quality is hard.

Special Issues

Improving Machine Learning Models with Specifications

The difference of testing machine learning models versus testing traditional software is that the action items for the latter is generally known after testing and could be executed with high precision, while for the former, we do not know how we will improve the model.

Suppose the model could already achieve high accuracy on the standard test set (it is indeed the train-to-train setting if we follow the WILDS paper), which means the model architecture, training objective, and hyperparameters are not responsible for the lower performance on the artificially created challenging set, the most straightforward way to improve the model performance is data augmentation. The naive way is to blindly collect more data that are wishfully relevant as an augmentation so we expect the performance could improve.

Guided Data Augmentation

However, this blindness hampers the efficiency of improving the models: the only feedback signal is the single scalar (i.e., failure rate) after we have trained and evaluated the model; we should have a feedback signal before we train the model.

- Unverified Hypothesis: the feedback signal is highly (inversely) correlated with the failure rate on the benchmark.

Formally, we have a list of specifications in the format of (s_1, D _ 1, D _ 1 ^ \text{heldout}), (s _ 2, D _ 2, D _ 2 ^ \text{heldout}), \cdots, the model \mathcal{M}_0 trained on D _ \text{train} does well on D _ \text{train} ^\text{heldout} but poorly on D _ 1 \cup D _ 2 \cup D _ 3 \cdots as indicated by failure rate \mathrm{FR}. We additionally have a new labeled dataset D _ \text{unused}. The goal is to sample D _ \text{unused} using (s_1,D _ 1 ^ \text{heldout}), (s _ 2, D _ 2 ^ \text{heldout}), \cdots: \mathrm{Sample}(D _ \text{unused}); we also have a random sample with same size \mathrm{RandomSample}(D _ \text{unused}) as baseline.

- Note: The D _ i and D _ i ^ \text{heldout} are completely different. For example, if the specification s _ i is operationalized through templates, these two sets are disjoint in terms of templates. What we are certain about D _ i and D _ i ^ \text{heldout} is that they are ideally sufficient and necessary with respect to s _ i; practically, the semantic underspecification of them are low [3].

There are a lot of things we could do with \mathrm{RandomSample}(D _ \text{unused}) and \mathrm{Sample}(D _ \text{unused}). For example

- Fine-tuning a model from scratch using \mathrm{RandomSample}(D _ \text{unused}) \cup D _ \text{train}.

- Patching the model using constrained fine-tuning [4] and related approaches.

Whichever method we choose, if we denote the intervention with \mathrm{RandomSample}(D _ \text{unused}) as \mathcal{M} _ 1 and \mathrm{Sample}(D _ \text{unused}) as \mathcal{M} _ 2. We expect the following conditions will hold:

- $D _ \text{train} ^ \text{heldout}$: $\mathcal{M} _ 0 \approx \mathcal{M} _ 1 \approx \mathcal{M} _ 2$.

- $D _ 1 \cup D _ 2 \cup D _ 3 \cdots$: $\mathcal{M} _ 2 \ll \mathcal{M} _ 0$, $\mathcal{M} _ 2 \ll \mathcal{M} _ 1$. That is, the specification-following data selection improves over the random selection on the specification-based benchmarks.

- Assumption: The samples x _ {ij} is fully specified by the specification s _ i.

- Note: If the annotations of a dataset strictly follow the annotation codebook, then the machine learning learns the specifications in the codebook. The process described above is a reverse process: we have a model that is already trained by others; we want to use the model in a new application but do not want to or can not afford to relabel the entire dataset, what is the minimal intervention we could apply to the dataset so that the model could quickly meet my specifications?

Detecting Inconsistent Labels with Specifications

Following the previous problem setup, we have a list of specifications in the format of (s_1, D _ 1, D _ 1 ^ \text{heldout}), (s _ 2, D _ 2, D _ 2 ^ \text{heldout}), \cdots; each specification has an unambiguous label. Rather than augmenting the D _ \text{train} with additional data by selecting using either (1) D _ 1 ^ \text{heldout} \cup D _ 2 ^ \text{heldout} \cup \cdots itself or (2) a model trained on it, we aim to correct labels directly in D _ \text{train} which are inconsistent with specifications.

Specifically, we could do the following for train, validation, and test sets:

- Note: It is important to note that the data splitting should happen before we correct labels; otherwise the scores between trials will not be comparable. An alternative is to use D _ 1 ^ \text{heldout} \cup D _ 2 ^ \text{heldout} \cup \cdots as the validation set so that all scores are comparable.

- Step 1: Grouping the specifications by the binary labels (for example, 0 and 1).

- Step 2: Using the queries corresponding to each label to rank samples D _ s; each sample in D _ s will receive an integer ranking ranging from 0 to \vert D _ s \vert. For example, for a set of positive specifications S^+, his will lead to a matrix of shape (\vert D _ s\vert, \vert S^+ \vert).

- Step 3: Merging the \vert S^+\vert (or \vert S^-\vert) ranking list into one list using some rank aggregation methods.

- Step 4: Removing all samples of label 0 (or 1). The top-k samples are the ones that should be corrected.

The main issue with this pipeline is that the number of corrected samples is strictly no more than k; retraining with only \frac{k}{\vert D _ \text{train}\vert} of labels changed may not have direct impact on the modified model.

- Note: This process is different from

cleanlabas the latter does not consider specifications (i.e., the guaranteed uncorrupted labels). Their setting is useful in many ways as their system only require noisy labels and predicted probabilities of each sample.

Reverse Engineering Queries Given Documents

For a DPR model trained on large corpus (for example, facebook/dpr-ctx_encoder-single-nq-base and facebook/dpr-question_encoder-single-nq-base), if we have a list of documents D that are aligned with our goal (or true underlying query) q, is it possible to search for its approximated version \hat{q} that returns D as relevant documents with high probability?

A somehow related problem called Doc2Query has been studied before; the difference is that these previous works use Doc2Query as a data augmentation (it is called document expansion in the IR community) approach.

With the vec2text, it may be possible to search for the best query in the embedding space using approaches like Projected Gradient Descent (PGD).

Geometry of Embeddings and its Implication for Text Generation

This is based on the hypothesis that there exists certain relation between the geometry of embedding space and semantic meaning of each point in that space. For example, sampling a convex set leads to sentences that have similar high-level specifications.

Many recent works show that text embeddings may be anisotropic: directions of word vectors are not evenly distributed across space but rater concentrated in a narrow cone; this peculiarity may not be related to performance [7].

Retrieval Augmented LM

RALM could be useful in numerous ways.

- Copyright: This is the idea of SiloLM, where the LM itself is fine-tuned with CC0 data. The copyright data is stored in a non-parametric database; these data could be incorporated into the inference process using RALM. However, with this design, the authors of the copyrighted texts could easily request a removal.

- Traceability: The retrieved samples serve as evidence to support the decisions made by the LM.

- QA: When we would like to do QA on a large tabular database (for example, asking “what is the percentage of patients who have allergy” to a large EHR database), the RALM is the most natural way to incorporate the necessary information in the database into the inference process of an LLM. Previously we need to build a pipeline that first generates queries written in formal language (for example, ElasticSearch queries) and then use these generated queries to answer the question.

These benefits are offered by the complementary nature of non-parametric databases’ high data fidelity and LMs’ inference ability. Specifically, the knowledge is stored distributionally in the LM; it is not straightforward to retrieve the exact know compared to using a non-parametric database. At the same time, the inference ability available to exploit in LMs are not available in other smaller models.

HateModerate

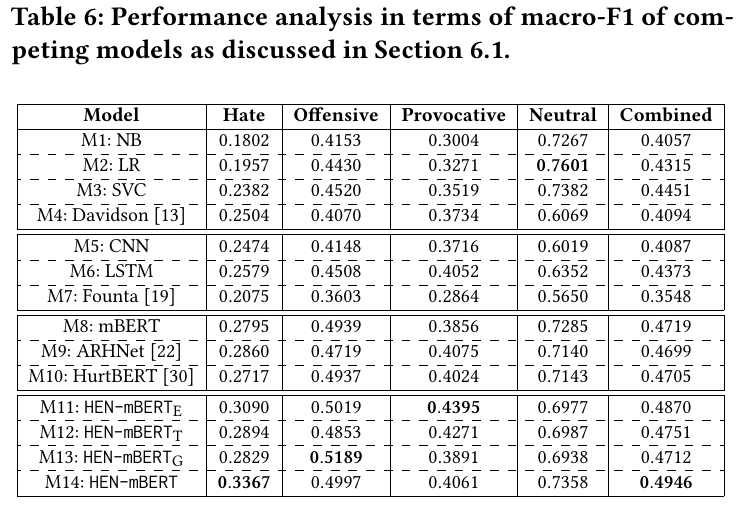

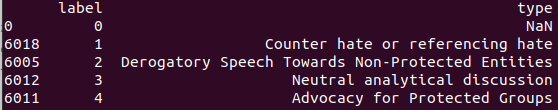

- Dataset Statistics

Label Inconsistency of Different Datasets

Given multiple datasets D_1, D_2, \cdots with the same input and output space \mathcal{X} \times \mathcal{Y} (for example, binary hate speech classification), is there a systemic approach that finds inconsistent labeling criteria. Specifically, if two similar sentences that belong to two datasets receive different labels, how do we explain the discrepancy in their underlying labeling criterion? This is done preferably in the format of FOL or natural language.

-

If we treat GPT-4 as an oracle and use it to annotate the samples from D _ 1, D _ 2, \cdots, we could obtain an accuracy vector of size \vert \mathcal{Y} \vert to characterize the label quality of each dataset. Note that for comparison purposes, the datasets to be annotated should be made same size and remains the original label distribution.

Previously it has been shown that using a simple zero-shot prompt shows an binary label inconsistency rate from 9% to up to 36%; the datasets under study are 15 hate speech datasets (uniform random sample of 200 samples per dataset) whose labels have been normalized to binary labels per each dataset’s description.

Note: The dataset label normalization process may be questionable.

Adversarial Attack on RLHF

We assume there is an underlying utility function U: \mathcal{Y} \rightarrow [-1, 1] that measures a response y‘s alignment to the input x: a response receives a high score when it is helpful, honest, and harmless.

- One thing we could do is investigating the relation between the ratio of reversed comparison pairs and the degradation on performance on the downstream tasks, such as HHH.

- The comparison reversal is not uniformly adversarial to the downstream tasks. If U(y _ i) and U(y _ j) is very close, then reversing them is not as effective as reversing another pair where U(y _ i’) and U(y _ j ‘) is very different.

OOD for Reward Model in RLHF

The reward model r(x, y; \phi) is fixed when fine-tuning the LM with PPO. There may be some distribution shifts between two stages. From the high level, this may not be an issue as the goal of RLHF is general enough (for example, HHH and Constitutional AI).

Applications of RLHF to Other Tasks

According to Hyungwon Chung, RLHF is the new paradigm to create application-specific loss function. It is therefore likely beneficial to abandon traditional cross-entropy loss altogether and opt for RLHF.

Pairwise Regression

This is especially useful for highly abstract tasks like hate speech classification. For example, we could initialize a RM and use the normalized score [0, 1] (for example, hatefulness) to fine-tune a hate speech regressor based on some open-source models. We could find a threshold on the validation set and then deployment the RM (with a threshold) to the testing environment. This idea is indeed the pairwise regression; it is one of three approaches (point-wise, pairwise, and list-wise) for learning to rank.

References

- ScAN: Suicide Attempt and Ideation Events Dataset (Rawat et al., NAACL 2022)

- A Computational Approach to Understanding Empathy Expressed in Text-Based Mental Health Support (Sharma et al., EMNLP 2020)

- Dealing with Semantic Underspecification in Multimodal NLP (Pezzelle, ACL 2023)

- [2012.00363] Modifying Memories in Transformer Models (Zhu et al.)

-

cleanlab- [1911.00068] Confident Learning: Estimating Uncertainty in Dataset Labels is the theoretical foundation of the

cleanlab; this paper has a blog. - [2103.14749] Pervasive Label Errors in Test Sets Destabilize Machine Learning Benchmarks is an application of the principle in the first paper to machine learning benchmarks; this paper has a blog.

- [1911.00068] Confident Learning: Estimating Uncertainty in Dataset Labels is the theoretical foundation of the

-

Doc2Query

- [1904.08375] Document Expansion by Query Prediction (Nogueira et al.)

- From doc2query to docTTTTTquery (Nogueira and Lin) and its associated GitHub.

- [2310.06816] Text Embeddings Reveal (Almost) As Much As Text (Morris et al., EMNLP 2024)

- Decoding a Neural Retriever’s Latent Space for Query Suggestion (Adolphs et al., EMNLP 2022)

- Is Anisotropy Truly Harmful? A Case Study on Text Clustering (Ait-Saada & Nadif, ACL 2023)